Regulators prod Enfield to face a flood that may never come

by Robert Lynch; March 3, 2024

Over 1,500 communities in New York State participate in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), Enfield Town Board members were told at their February meeting. Enfield is among only nine that do not. But presumably, not for much longer. State Government won’t allow our town to remain a lonely outlier, an NFIP non-participant, as it has been for decades, even though flood risks here arguably remain minimal.

“This is a voluntary program at the federal level, but in New York State participation isn’t exactly voluntary,” Brienna Wirley, a regional representative for the state’s Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) Flood Plain Management Program, advised the Town Board February 14th. Environmental Conservation Law “actually designates and requires that local communities that have identified flood risk are required to participate in the (NFIP),” she said.

No, Enfield Creek hasn’t changed. Nor have regulators altered the law. The only thing that’s different now is Uncle Sam’s eyesight.

“You never had maps before. You have maps now,” Thomas Song of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) told the February Town Board meeting. “Regardless of whether you join the NFIP or not, the Town of Enfield was mapped-in.”

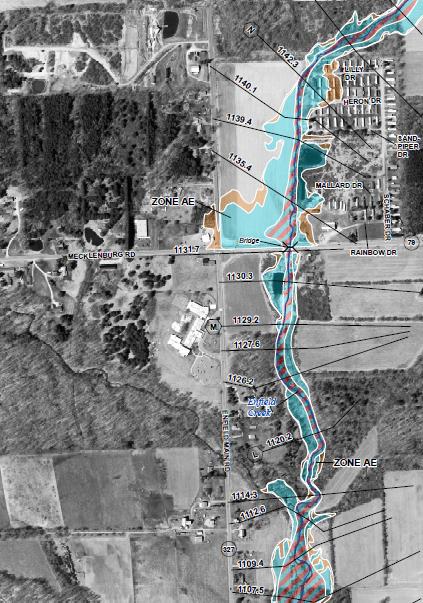

For the first time, FEMA has included the Town of Enfield in its flood plain mapping program. And with the new maps come new requirements, although they’ll only impact a few. FEMA mandates that people who live in the newly-identified Enfield Creek flood plain and who have federally-backed mortgages buy flood insurance. And to join the NFIP so that residents can purchase the insurance at federally-subsidized rates, the Town of Enfield must enact new laws to tighten development in flood-prone places.

Only about 20 homes stand in the Enfield Creek’s flood plain, as newly-mapped by FEMA. The agency’s preliminary maps show many of those homes as single-wide trailers lined up side-by-side at the western ends of Lilly and Heron Drives in the Sandy Creek Mobile Home Park. Flood maps also include homes east of Enfield Creek where Enfield Center Road crosses it.

Wirley said the DEC hasn’t the money to notify the affected residents itself. So the Town of Enfield will do so instead. Board members in recent days authorized letters go out to affected residents, informing them of a further Town Board discussion of the flood maps at its next meeting, March 13th.

From what was told the Town Board in February, federal officials had never thought of Enfield as having a serious enough flood risk to warrant mapping. When federal authorities last compiled maps in the 1980’s, Enfield got overlooked. But when the agency switched to mapping on a countywide basis, Enfield got roped in. Now the Town and its handful of impacted residents must address the flood risk problem.

“If they have a mortgage, and that mortgage has any kind of federal backing, their lender will come to them and require that they buy flood insurance,” Song cautioned the Town Board.

And as for the Town, Song advised, “If you are not a participant in the NFIP, federally-backed insurance will not be made available to those folks.”

Flood insurance would still be available from other providers, Song acknowledged. But he implied that policies not backed by federal subsidies carry higher premiums and are harder to obtain.

Yet, according to the state conservation representative attending that night, Enfield’s opting-out of NFIP really isn’t an option, nor is ignoring the tougher flood plain management practices that the DEC dictates.

“Even if a community was choosing not to participate, you would still be obligated to enforce the building code within your community which has all of these requirements for structures included,” Wirley said. “The community is required to regulate all development within the FEMA-identified flood hazard areas, otherwise known as the 100-year flood plain.”

The construction mandates, outlined in Section R322 of the New York State Building Code, set strict limitations on how anything new or a “substantial improvement” to an existing structure can be built in a flood plain. A home could be built on “posts, piles, or piers,” Wirley said. A first-floor foundation could be laid up, but then used for parking only. State regs prohibit below-ground basements in flood zones. Crawl spaces strike a fine line on which the rules sometimes conflict. The ground floor of any livable space would need to rise at least two feet above any “100-year” flood line.

And in the most-restrictive area, the “floodway,” you likely couldn’t build much of anything, absent securing what Wirley described as a “no-rise or encroachment review,” signed-off by a state engineer.

And once a town adopts its more restrictive ordinance,” Wirley said, it needs to enforce it.

“Isn’t this essentially back-handed zoning?” this Councilperson, Robert Lynch, asked Song and Wirley after more than half-an-hour of back and forth.

“I don’t how to answer that question,” a seemingly blindsided Thomas Song replied. “The federal government has no jurisdiction over local land use decisions, so we’re not part of your zoning process,” he explained. (Of course, Enfield has no zoning.) “What we’re showing is where your flood hazards are, and there are requirements, so I guess you could be right.”

“To put a basement in an area that would be inundated with water would just be asking for trouble,” the FEMA representative insisted. “It would create an unsafe living environment for the inhabitants.”

At times during the meeting, the flood insurance team of two sounded like they hadn’t gotten onto the same page beforehand. The DEC’s Wirley stated the law demanded Enfield join the NFIP, then discussed community consequences should it not do so, consequences like the additional expense of repairing or rebuilding flooded structures and the costs and risks imposed upon first responders performing flood rescues. Does Enfield really have a choice but to comply? It arguably remains a gray area.

Section 36-105 of Environmental Conservation Law provides a bit of clarity. It states that a government like Enfield, newly-notified as being flood-prone, “shall promptly, within the time frames required by the national flood insurance program, apply for and complete all requirements for participation in the (NFIP).”

But what about penalties? Section 36-109 of the same law states only that a jurisdiction’s failure to participate may bring to it sanctions limited to its ineligibility for federal flood disaster aid, ineligibility for “federally provided loans or federally-guaranteed financing,” and that its residents would be denied NFIP insurance. No mention is made of the town being fined or its Board members hauled off to jail.

Nothing resulting from the new FEMA maps requires those living outside Enfield’s limited flood zone to buy flood insurance nor mandates that those living within the zone buy policies if they don’t have a mortgage. State law considers a “federally-backed” mortgage broadly, including a mortgage written by any institution backed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). So just about any mortgage held by any bank would trigger the flood insurance mandate.

But stepping back serves a purpose here. Thomas Song and Brienna Wirley talked mostly like the Susquehanna River was slithering through Enfield, rather than a country stream that where it sidles past the trailers at Sandy Creek Park carries little more water than a farmer’s ditch. Is everyone making much ado about nothing—or at least, about very little?

The flood plain of Enfield Creek is narrow. True, at one point, the “100-year” flood plain would cover much of the field northeast of Miller’s Corners. But interestingly—and for New York State, conveniently—the flood study downstream terminates before Enfield Creek reaches Robert Treman State Park.

Moreover, as this Councilperson brought to everyone’s attention, FEMA considered only Enfield Creek; not “Five Mile Creek” that flows under NY-79 at the bridge west of Millers Corners, nor the creek that passes under Route 327 near the Trumbulls Corners Road intersection. Fish Creek escapes attention. So does the stream that flooded a decade ago and washed out the Bostwick Road culvert at the “School House Dip” east of Cole Grove.

“Is it too restrictive, or is this not restrictive enough?” this Councilperson asked Thomas Song, observing the arbitrariness in what had been presented us. As to the “School House Dip” flood, I remarked, “The culvert had to be replaced, and there is a house right in the area, and I saw water going right across that lawn.”

Thomas Song hedged. He said creeks were chosen based on conversations maybe five years ago with Town officials, leaders presumably long gone.

Song said the Bostwick creek may have been too small to consider. But he added, “If this area is known for flooding. I think it would behoove the community to make sure that any permits for development in this particular area would meet a higher standard.”

Song did assure the Board that if Enfield joined the NFIP, any property owner, and not just those in a designated flood zone, could purchase federally-backed flood insurance and receive benefits in the event of a flood.

And, then again, there’s the issue of a 100-year flood.

“We’re talking once in 100 years,” this Councilperson told the FEMA and DEC invitees, eager himself to put the flood fears that at times approached apocalyptic proportions into proper perspective.

“No sir; and the terminology is terrible,” Thomas Song answered this writer, in what one could argue skewed statistics to promote a desired outcome.

“The one per cent or the 100-year flood, it does not have to be a single event,” Song sought to qualify. “It’s like having a bag of 100 marbles; 99 of them are white, one of them is red. And every time you have a storm, you stick your hand in and you pull a marble out, and you have a one per cent chance of getting that red marble. But if you did, you still throw it back in the bag, and that next storm you can pull it out again.”

Mind you, the U.S. Geological Survey doesn’t define a “100-year flood” quite that way. If that one-per cent chance occurred every time it rained, a flood of once-per-century magnitude would demand redefinition to a status of far greater frequency. Brienna Wirley put the percentage more accurately.

“If you have a 30-year mortgage on your house, there’s a 26 per cent chance of that structure flooding during that 30-year period,” Wirley clarified.

Yes, but also a 74 per cent chance that it won’t flood. Once knowing the numbers, is the risk really worth the bother and expense of building a creekside home on stilts? Maybe to those with the money, it is. Just remember, we’re talking flood insurance here. And insurance companies love to err on caution’s side.

The flood maps Thomas Song presented Enfield’s Town Board February 14th are not yet final, though there’s little doubt FEMA will adopt them largely as they now stand, probably this summer. Once the maps get approved, individual property owners can raise specific objections. A 90-day comment period that began in late-January is primarily to invite municipal input, if any.

And although this Councilperson urged Enfield to brace for its compulsory inclusion in the NFIP and to encourage its Planning Board to start work on draft regulations, the FEMA and DEC representatives attending that night urged the Town to hold off adopting a specific ordinance until the maps become final, as boundaries might yet change, and if they did, the ordinance’s particulars would need to change too.

But “thinking like a banker,” I interjected, might lenders demand that those in the preliminarily-charted flood zone purchase flood insurance now, insurance Enfield’s lack of enabling legislation doesn’t allow them to buy?

“I can’t speak on behalf of the lenders,” Song qualified, “I don’t know if they have standing to do that?”

“But the banker has standing to say ‘no loan,” I rebutted.

And with that remark, Town Supervisor Stephanie Redmond hustled us off to the agenda’s next topic. We’ll revisit flood insurance March 13th.

###