by Robert Lynch, July 22, 2023

Enfield Supervisor Stephanie Redmond’s worst environmental nightmare got some fresh talk-time this past Tuesday at the Tompkins County Legislature. Some might regard it as no more than an offhand, throw-away remark. But Redmond and many of her neighbors here in Enfield may take it more seriously.

“We’re sending our waste to somebody else’s back yard, the Town of Ithaca’s Amanda Champion told her fellow legislators at their Tuesday, July 18th meeting. “So personally I think if we want to deal with the problem ourselves, we should have our own landfill and figure out where we’re going to put that in our county. And then we’re all going to be responsible for our trash.”

“Is that a motion?” Danby’s Dan Klein, the evening’s presiding officer, asked.

“I’m pretty sure that would not pass,” Champion smiled back.

And there Champion’s idea pretty much ended.

Admittedly, Amanda probably broached the prospect of a local landfill half in jest. But casual words can speak to heartfelt convictions. That’s how seeds get planted for ideas yet to grow.

Champion’s suggestion arose as a sidebar to a more substantive resolution before the County Legislature Tuesday night. It would have begged New York State neither to extend the life of the giant Seneca Meadows landfill north of Waterloo nor to grant the landfill operator’s request to pile it taller. The resolution won a plurality of legislator support, but lost for lack of a single, eighth supportive vote. With Legislature Chair Shawna Black excused—likely stuck in an airport somewhere, heading back from foreign travel—her vote could have made the difference. Black could potentially return Tuesday’s Resolution for a revote at some future meeting.

But Champion’s casual talk of a new landfill, apart from showcasing the legislator’s lack of institutional memory, may sound alarm bells for those in Enfield. Before our county decided decades ago to close its local dumps and transport all of our garbage to its neighbors, it briefly bandied about the idea of a new landfill site off Enfield’s Bostwick Road. Add to that the common recognition that landfill sitings often find their way to the bottom of any county’s economic food chain. And that, for us, would be Tompkins County’s poorest town, our little Enfield.

It was only last summer when Supervisor Redmond raised the prospect, seemingly out of nowhere, that if Seneca Meadows were to close—and current regulations say it must close by 2025—its owners, or commercial operators like them, could target Enfield and build the Waterloo landfill’s successor here.

“I would not like to see a landfill anywhere in our town,” the Supervisor emphatically told her Town Board at its meeting in July of last year. “The one up at Seneca Meadows is noxious; fumes for miles around; it smells terrible.”

That it does. Reportedly, it’s the largest landfill in New York State. Seneca Meadows, now operated by a Texas-based company, spreads its rotten-garbage odor for miles in all directions. Travel to the Del Lago casino or to the Waterloo Outlet Mall, and you’ll smell it. Take pity on the locals who must whiff the stuff constantly. And critics told the Legislature Tuesday that cancer rates have ticked up in that region.

Redmond had raised her remarks last year as she’d cast aloft a short-lived trial balloon for a potential zoning law in Enfield, one that might prohibit landfills and also restrict solar farms. Since then, she’s settled on more modest land-use control, with no more landfill talk.

Yet while most of us in Enfield take no joy in what Seneca Meadows has inflicted—and continues to inflict—upon the northern part of our adjacent county, we in Enfield may hold a valid ulterior motive for keeping New York State from closing it down. To the point: Better it stay there than come here.

“Amanda, you scared me to death,” Dryden legislator Mike Lane replied to Champion regarding her idea for a new, local landfill. “Please, almost 35 years ago, we went through all of this,” he recalled.

Lane, perhaps unlike Champion, remembered the protracted local debates that led to the closing of Tompkins County’s small-scale, ground-polluting landfills off Hillview and Caswell Roads, the latter landfill in Lane’s own Town of Dryden. “They were small, rinky-dink places,” legislator Mike Sigler described them both at the meeting.

Enfield’s two legislators, Anne Koreman and Randy Brown, each supported sending New York’s Department of Environmental Conservation a message that it deny Seneca Meadows’ request to extend the landfill’s life by 15 years, namely to 2040; or to allow it to increase the garbage mound’s height by 70 feet. “Mount Trashmore,” as locals call it, is already as high as a 30-story building, environmental advocate Evonne Taylor reminded lawmakers.

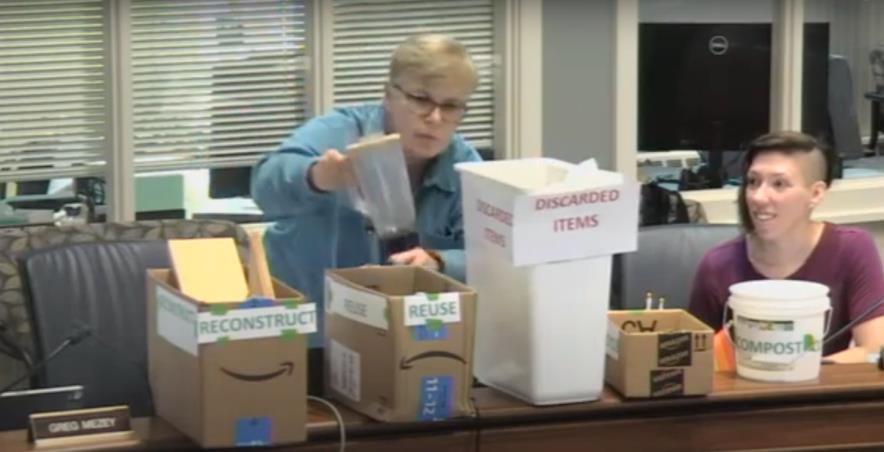

To advocate for adoption, Enfield-Ulysses’ Koreman brought “show-and-tell-time” to the Legislature Tuesday. She set upon her desk a basket and several boxes to demonstrate how much of what we call “garbage” can be held back from the landfill with only a bit of thoughtful planning and constant discipline. Lumber can be repurposed; uneaten food composted; worn-out electronics recycled, she said.

“So really what’s left is not much,” Koreman concluded. By then, the garbage basket she’d relabeled “Discarded Items” sat nearly empty. (Koreman spared us the visual of sprinkling before us any spent litter from her beloved pet cat.)

But Koreman’s demonstration underscored an important point: Tuesday’s Seneca Meadows debate dealt with not one, but two at times conflicting objectives; one aspirational, the other grounded, immediate, and practical. Yes, in the long-term, try to reduce the garbage stream altogether. But in the short run, how do you get rid of the mess you’ve just made today?

First, to the future: “I actually think we can be more ambitious” than current plans propose, Koreman said. She’d set a goal of reducing waste reduction by “80-90 per cent. ” She’d “create a circular economy.”

But waste reduction at that level would impose economic hardships and probably require a much more intrusive government.

Take building waste: “We get charged by the ton, and construction debris is very heavy,” Koreman reminded us, as she pulled from her “discarded items” basket a short, clean plank and plunked it in a repurposed Amazon carton labeled “Reconstruct.” Yet contractors will tell you they must toss perfectly good, once-used lumber into the dumpster because it costs too much to pay workers to pull out the nails.

And it would also take an overbearing army of garbage police, armed with books of pricey appearance tickets, to force homeowners to sort methodically their throwaways so as to meet the Ulysses legislator’s exacting standards.

“We should really be aggressive in trying to move the needle on our citizens taking this up as an important part of addressing climate change that can be addressed within people’s lives,” legislator Rich John said in agreement with Koreman’s aspirational goals.

But in the end, Rich John got practical. He voted against the Resolution to intervene in the DEC’s Seneca Meadows review.

John bluntly described Seneca Meadows this way: “It is gigantic and it doesn’t smell great. It’s imposing. It is a landfill.” But, he added, “I don’t know we are addressing the issue at all by saying close Seneca Meadows.” Rich John would rather Tompkins County expend its energy—and its advocacy—pressing New York regulators to develop a plan to solve the garbage crisis altogether.

“I have some skepticism there given—pick your topic—of New York State trying to execute complicated things,” John lamented. For example, he noted that New York first banned sending adolescent offenders to prison, but then couldn’t find any other places to detain them.

As for Seneca Meadows’ fate, John faced reality. “Our garbage will go to someplace else; that may be better, may be worse; we don’t know.”

“I think it’s a matter of responsibility,” Newfield-Enfield’s Randy Brown argued in the resolution’s support. “If we just continue to build these landfills, then we’re not going to move forward and control our waste.”

“No, Randy, I don’t think it’s responsible to call for the closing of something that is actually needed,” Mike Sigler, Brown’s fellow Republican, countered. “It’s irresponsible, in fact.”

And addressing Champion’s home-based solution, Sigler’s said, “Build your own landfill? I don’t think there’s any town in Tompkins that’s going to get on board with that.”

Certainly not Enfield, based on Redmond’s last year’s remarks.

Sigler also raised the economic argument to justify the regional landfill’s continuation. The farther away the landfill gets, he surmised, the more it will cost to ship garbage there. And the greater the expense, the more likely the frugal will find work-arounds.

“You will find a couch in the forest… tires next to the side of the road,” Sigler predicted.

Lansing’s Deborah Dawson closed the nearly 40-minute Seneca Meadows debate with a dead-accurate observation:

“I think this landfill sucks,” Dawson said of Mount Trashmore’s behemoth of a stinky garbage pile. “But I don’t think people are going to stop generating garbage, because if we close the landfill, I think that’s putting the cart before the horse. I think we ought to be looking at things we can do.”

Do what you wish, County Legislature and New York State. Just please, as Enfield’s Supervisor would admonish you, don’t build a second Mount Trashmore anywhere close to us.

###