Enfield regulations impair our freedom, critics charge

by Councilperson Robert Lynch, May 26, 2025

“I don’t think anybody wants flood insurance. What they want is to be able to get a mortgage.”

Enfield Supervisor Stephanie Redmond, Town Board meeting, May 14.

“It seems like a bunch of bull to me.”

Enfield landowner John Rancich, same meeting.

****

Rosanna Carpenter’s and Rodger Linton’s log home lies at the edge of—but just beyond—the newly-designated Enfield flood prevention zone. You need to cross a private bridge to reach their residence. Carpenter and Linton maintain that bridge. They also own land each side of it, vacant fields that could someday sprout new houses, if only government will tell someone it’s OK to build there.

Right now, Carpenter and Linton are angry. And they brought their discontent to the Enfield Town Board earlier this month. Others living or owning land in the flood plain did so as well. They didn’t like what the Town Board did that night.

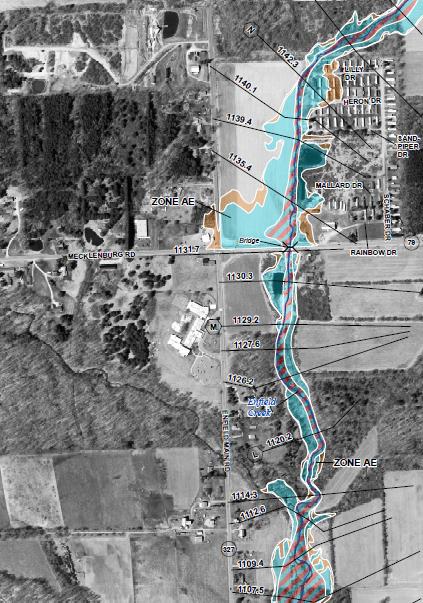

Federal and state authorities last year decided that a narrow strip of lowland along Enfield Creek could someday get flooded, even if no more often than once in 100 years. And because of that remote risk, state officials successfully strong-armed the Town Board May 14 to enact new, stringent flood plain development controls in what they call the “area of special flood hazard.” New buildings there could have no basements, and many might need to be built on stilts.

The tighter rules accompany Enfield’s forced participation in the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Federally-supported flood insurance will be available to all Enfield homeowners as of mid-June.

People like Carpenter and Linton argue that neither the regulations nor the insurance is needed, and that the government controls smack of first-ever, Enfield zoning.

Flood insurance rates run three-times the average of a homeowner’s policy, Carpenter said at the May 14 Public Hearing called to address the proposed law. The hearing ran just five minutes short of an hour and filled nearly all the room’s chairs. “So if you have a $2,500 policy on your home, it’s going to cost you $10,000 a year to take the chance that you might get flooded,” Carpenter estimated.

“Has anyone ever drowned in this town from a flood?” Linton asked rhetorically. “Has anyone even been made sick from a flood, ever? Can anybody answer that question for the Board?”

This Councilperson said he couldn’t recall any deaths. The criticism continued.

“My apartment buildings are in the flood plain. They’ve been there for 35 years, and I’ve not had any floods” John Rancich, Enfield’s best-known landlord, informed hearing attendees. “I’ve had the creek come up a little bit, but there’s never been a flood.”

“It seems like a bunch of bull to me, and the town doesn’t need flood insurance,” Rancich asserted.

Need it or not, federally-backed flood insurance will soon become available to every Enfield homeowner. And a few residents may even be forced to buy it.

The Town Board’s adoption of the controversial regulations May 14 fulfills a federal and state requirement that governmentally-backed—and yes, pricey—flood insurance be made available to everybody in Enfield now that federal and state regulators have identified a flood-prone place in the Town. That strip along Enfield Creek may be small. It includes only a handful of houses. Nonetheless, its existence suffices for the government’s mandate to kick in.

The leverage government holds is that as of mid-June anyone owning property within the flood plain will need to purchase flood insurance to qualify for a new, federally-backed mortgage or to hold onto a mortgage already held. The mandate covers financing from any bank insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC).

The Town Board’s vote to adopt the Flood Damage Prevention Law was four-to-one. Councilperson Robert Lynch (this writer) cast the only dissent and took pains to explain why he’d done so.

“There wasn’t one person at this meeting tonight, at the public hearing, who said they want to buy flood insurance, not one” Lynch took note. “And I didn’t hear any person who said, ‘I’ve got a federally-backed mortgage and I need to buy flood insurance.’ I didn’t hear that either.”

Instead, Lynch said, “I heard people saying if I’ve got a federally-backed mortgage, and I’m required to buy flood insurance, I’m going to get financing somewhere else. That’s what they’re saying. I’ve gotta’ listen to what the public says.”

Town Supervisor Stephanie Redmond took a different view. “I don’t think anybody wants flood insurance,” the Supervisor asserted. “What they want is to be able to get a mortgage. That’s the reality of it. It’s hinging on a mortgage.”

But the public’s mood of the night was anger. Quite plainly, what came from the visitors’ gallery was defiance.

“You’re condemning people’s property,” Roger Linton asserted. He zeroed-in on a stronger-than-state-requirement that Enfield had initially proposed—but later in the meeting withdrew from the law—that would have banned any new residential construction within the flood zone. “You’re making their property worthless,” Linton admonished the Town Board.

“I’ve not heard anything here or what I’ve read that’s going to help anybody in this town,” Marie Vandemark, whose family owns Sandy Creek Mobile Home Park, said. Some of Sandy Creek’s manufactured homes rest within the flood plain.

“Look, boilerplate or not, you do have some power here; you do have a small voice, and I would love to see you all, individually or as a collective group, say, ‘Look, State of New York, or whoever you’re talking to, this isn’t really suited to our town. We have a very small population, and a small group of residents that are going to be affected,’” Vandemark said.

Other voices joined her. “Now they’re going to pass a law about flood insurance that I’m going to have to buy that I don’t need,” landlord Rancich lamented. “It’s no big deal to me. I’ll just raise my rent. And so, once again, there’ll be more cost to people that are renting my apartments, because the Town wants flood insurance that they don’t need.”

“We’re asking you to fight for us,” resident Donald Head instructed the Town Board.

“There’s nobody here in favor of this,” Linton informed Enfield’s lawmakers. “I haven’t heard one single person speak in favor of this. They don’t want it… Stand against it.”

“Go into violation,” Rancich dared the Town.

“If we don’t adopt the law, then the Attorney General of New York can come in and force us to adopt the law,” Councilperson Jude Lemke cautioned. Of anyone that evening, Lemke offered the harshest prediction of state retribution. A lawyer herself, Lemke relayed advice from the attorney for the Town, Guy Krogh.

A plain reading of statute, on the other hand, provides a more benign interpretation of potential punishment. True, New York Environmental Conservation Law does prescribe that a town like Enfield, newly-designated with a flood hazard area, must “promptly… apply for and complete all requirements for participation in the national flood insurance program.”

But the “sanctions” meted out for non-compliance under that same article of conservation law fall short of the draconian punishments Lemke quoted from attorney Krogh. Statutory sanctions, the text states, limit themselves to the inability for residents to secure FDIC-backed mortgages, and, the law states, “in areas of special flood hazard, ineligibility for flood disaster aid.”

Obvious to many, Councilperson Lemke attempted to read the penalties more expansively, implying a wider, town-wide impact. At one point, she inaccurately warned that failure to adopt the Enfield law could place everyone’s home mortgage at risk of cancelation. Lemke later corrected herself.

“We as a Town and the residents of the Town will not be able to apply for federal funds if there’s a presidential disaster declared that we will not be able to participate in and get funds from the federal government, not just for floods, but for any federal disaster,” Lemke said.

The lawyer-Councilperson relied heavily upon an email circulated to Board members only hours before the meeting and signed by Kelli Higgins-Roche, New York State Coordinator for the NFIP. Some Town Board members (including this writer) had not read Higgins-Roche’s letter. But a careful reading of that letter afterward suggests some meeting night exaggeration. The NFIP coordinator’s admonitions confine themselves to mortgage availability and to grants and disaster aid specific to “identified flood hazard areas” or to municipal flood prevention in general.

In many ways, a healthy dose of misinformation circulated about the meeting room that Wednesday night.

“People who are in the flood hazard zone will be required to purchase the flood insurance,” Councilperson Lemke stated at the hearing’s start.

Not so. No property owner in the flood zone, including Stoney Brook Townhouses’ owner John Rancich, will be required to buy flood insurance, unless he or she holds a federally-backed mortgage, one that the bank is forced by the feds to insure.

“This has an impact on the Town as a whole,” Lemke continued. “It will limit our ability to receive any funds from the federal government.”

Any funds? That’s an ambiguous assumption. Higgins-Roche’s letter does not state such a categorical denial, unless the funding relates to flood relief and mitigation.

Town Supervisor Stephanie Redmond cautioned that failure to adopt the regulations could imperil an already-awarded grant to a near million-dollar culvert project for Bostwick Road, and also to a forthcoming application to replace a second culvert, its location under Rumsey Hill Road. Still, the Bostwick Road replacement is state-funded, not federal.

“There are no direct fines imposed on the communities for not complying with [Article 36 of Environmental Conservation Law],” Higgins-Roche conceded, “but there may be other grants at a state and federal level that the Town would be ineligible for due to lack of NFIP participation.” She did not specify the endangered state grants.

Let’s “strip this law down to its skivvies,” this Councilperson indelicately stated. Before its final vote, the Town Board adopted two, separate amendments to the Flood Damage Prevention Law. First, it removed the absolute prohibition on new residential dwellings in “areas of special flood hazard.” Then, the board similarly excised a prohibition on placing new manufactured homes in flood zones. As amended, the Enfield law stands no more restrictive than New York State’s model ordinance.

The number of properties within Enfield’s flood zone varies based on whom you ask. The NFIP coordinator puts the number at “about 20.” A Tompkins County Planning Department spreadsheet lists only six. Town Clerk Mary Cornell said she’d notified about eight people.

“The public is not fully informed about what you guys are doing,” Carpenter complained. “No one knew anything about this law,” she alleged, after having gone door-to-door. “You can’t pass a law that they don’t even know about,” Carpenter scolded the Town Board.

Town-wide flood insurance availability and the individual mortgage protections that hinge upon it became central arguments to flood law supporters during board member debate.

“Anybody in this town can buy flood insurance, if we participate in this program, whether they’re in the flood zone or not,” Lemke stressed as she promoted the new law. If the Town declines participation, flood protection policies won’t be available to those on high ground or low, she said.

“They haven’t been able to buy flood insurance now, before the designation, because we weren’t an NFIP member,” this Councilperson reminded his colleague. So nothing much would change for most people.

“So if anybody was close to a flood plain and wanted to buy flood insurance, they would not be able to unless we adopt this,” Lemke answered.

“And I don’t hear anybody saying they want to buy flood insurance,” Lynch rebutted. “But I’m hearing a lot of people say we don’t want the regulations.”

Town Supervisor Stephanie Redmond was home ill, but she zoomed in to participate minimally and to vote. Redmond directed her concerns to the mortgages, and her pointed criticism to this writer-Councilperson.

The Supervisor worried about people in the flood zone who hadn’t known of the hearing, about those who might suffer unplanned hardship and later need a mortgage they couldn’t then secure for lack of insurance; and about those whose relative may die and force a home’s sudden sale.

“And I’m sorry, but people aren’t walking around with like $300,000 of cash on hand,” Redmond said.

“Yeah, I understand why people don’t want to all of a sudden, you know, be in a flood zone, but the reality is they are in a flood zone… and there’s nothing this Town Board is going to do to make it not a flood-zone,” the laryngitis-stricken Supervisor said with what little voice she could draw forth.

“But where are they tonight?” this Councilperson, Lynch, queried. “They aren’t in this room. None of them are here. The people who were here say we don’t want the regulations.”

“But we have an obligation to all the residents of the Town, and we have an obligation to uphold the state law,” Lemke interjected.

More than an hour after the hearing had ended, and after the Town Board’s own 20-minute discussion had run its course, the clerk called the roll, and Councilperson Cassandra Hinkle, quiet through most of what had transpired, waived off casting the first vote. Only after Supervisor Redmond had voted her own affirmation did Hinkle do so as well.

“Honestly, I hate this too,” Hinkle said of New York’s strong-arm mandate. “It is the state coming down on us for it. So what could we do as an alternative? Fight it as Enfield? No. To what end?”

“Freedom! Property Rights!” two voices erupted from the gallery.

“People are going to lose their house. They’re going to lose their mortgage and lose their house,” Redmond reacted from her virtual perch on the big screen. “That’s no freedom. That’s unhoused.”

###