Equity Officer’s job gains permanence in close legislative vote

by Robert Lynch; December 6, 2025

In this age of Trump, one could argue the Tompkins County Legislature last Tuesday painted a big, blue bullseye on this community’s backside. Yes, it may have done so. And if it did, you can credit (or blame) Newfield-Enfield legislator Randy Brown for having brought the blue paint.

Because and only because Brown, a Republican, switched his vote from no to yes at the last minute did the Legislature muster the minimum eight votes it needed December 2 to elevate the job of Chief Equity and Diversity Officer (CEDO) to a permanent place within the Tompkins County Charter.

“If we want to say that Tompkins County believes in inclusion… if we want to continue backing up what we’re saying about having a diverse and equitable and strong workforce, we need to add this position to the charter,” Amanda Champion, Chair of the Government Operations Committee and prime sponsor of the charter-changing local law, advised colleagues as she brought the measure to the Legislature’s floor.

“The CEDO brings the tools and the knowhow and the training and the coaching and the listening and the policies to embed this into the way we do things,” legislator Veronica Pillar, like Champion, one of the body’s most activist liberals, echoed her fellow Democrat’s endorsement that night. “The CEDO is how we operationalize our values,” Pillar said.

On the one hand, the addition of a CEDO as a charter-bound administrator constitutes little more than window-dressing; symbolism over substance, a transparent tip of the hat to political correctness. But on the other hand, Tuesday’s action grants the equity officer an ongoing degree of institutional tenure. Future legislatures will find it next to impossible to eliminate the post should finances tighten or political winds shift.

The Tompkins County Legislature created the equity officer’s position in late-2019 and filled it the following year. The CEDO answers to the County Administrator. Two people have occupied the job since it was established. There was a long gap between when the first CEDO, Deanna Carrithers, departed in mid-2022 and when her successor, Charlene Holmes, took over in September 2023.

This past October, Holmes herself resigned, quietly exiting without disclosing her future plans. The position again remains open. Administrators hope to fill it in January. They reportedly have 25 applicants.

Chief equity officers stand as a rarity within county governments of our size. When Tompkins County’s legislators created the job six years ago, the only similar position in governments upstate, we were told, was in Buffalo.

Perhaps gun-shy to the likelihood of political pushback, few, if any, have called over this past half-decade for the CEDO position’s elimination. Yet some of the Legislature’s more conservative members have at times questioned the officer’s goals and initiatives; even the way the appointee chooses to write. Those subtle critiques drew from Enfield-Ulysses legislator Anne Koreman during Tuesday’s discussions an impassioned rebuke.

“There is more scrutiny over this position than any position that I’ve seen in my eight years (on the Legislature) and it is really upsetting to me,” Koreman told those beside her, her voice cracking with anger. “I don’t know how else to describe it except it’s a prejudice in itself, and we need to take a hard look at the scrutiny that we are putting on the person in this position,” Koreman counseled.

How Randy Brown came to change his planned vote against the CEDO position’s charter codification Tuesday could be viewed by some as one man’s surrender to racial and gender shaming.

As the hour-long legislative debate meandered toward a vote, the charter change’s supporters quietly counted noses, speculating how members would fall on the issue, even those who hadn’t spoken. Randy Brown had already telegraphed his intent to oppose. Supporters sensed they’d lose. They pleaded for at least one opponent to defect. At that point, Lansing’s Deborah Dawson brought out the heavy artillery.

“I don’t often find myself in my colleague’s camp chastising all the old white guys,” Dawson proclaimed, tapping Amanda Champion on the shoulder as she spoke, “But this is not going to look good if this vote comes down to women and our one man of color and our one gay white guy voting for it and everybody else going, ‘Oh, no; can’t do that.’ Think about it. Is that what you want? Is that how you want to be viewed?”

And yes, if you’re one of those who counts by race, gender, and sexual orientation, that’s what it would have looked like. Supporters Dawson, Koreman, Champion, Pillar, and Shawna Black are all female. Travis Brooks is black. Greg Mezey is gay. That’s seven votes, one short of the eight needed. All the remaining legislators are straight, white men and all had planned to vote no. (Dan Nolan wasn’t present. His Zoom link had cut out.)

No one budged. And then Randy Brown did.

“You know, I’m going to change my vote,” Brown announced. “I think it’s going to happen anyway next year,” the Newfield legislator predicted of codification, remarking at the time that he’s always thought of himself as a “mutt,” part Native American. Brown credited his native heritage for influencing his decisions.

If anything, the new, larger Legislature, set to be seated next month, may be more liberal than even the one at present. And it requires only a simple majority to change the charter. So Brown surmised that if the current body didn’t codify the CEDO position , the one that followed it likely would.

“I do think we do need to go through the charter and clean it up, without a doubt,” Brown added. Any significance to his switched vote he left understated.

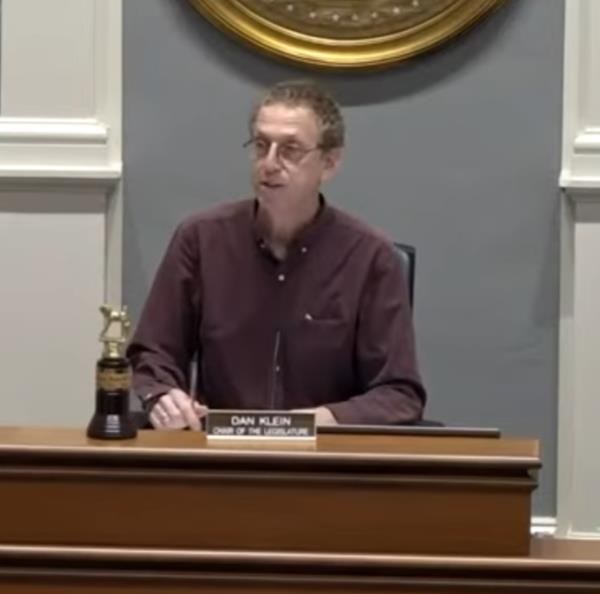

Brown’s fellow Republicans, Mike Sigler and Lee Shurtleff, never spoke during the protracted, one-hour debate. Each would eventually vote against CEDO codification, as would Democrats Mike Lane, Rich John, and Legislature Chair Dan Klein.

And while Deborah Dawson had observed that a united straight white guy vote would send everyone the wrong message, Klein countered that assertion. He alleged that putting the CEDO into the charter would send its own toxic message, one not well received by power brokers elsewhere.

“The President has taken the stance that anywhere the term DEI appears it must be eliminated, and I do not agree with that stance,” Klein reminded legislators, reading from a prepared script. “However, I feel like some people here have taken the opposite position; anytime the term DEI appears, it is sacred and should not be examined or questioned or discussed, and I do not support that stance either,” the Chairman maintained.

“For me, I do not see any evidence that our Chief Equity and Diversity Officer position has improved any measure of diversity, equity or inclusion in our organization,” Klein insisted, the Chair rationalizing his opposition to placing the job of CEDO within the county charter.

From the visitor’s gallery at meeting’s start, eight supporters of the charter change spoke or wrote messages in support of the CEDO-inclusive local law. Those eight included several County employees and a couple of newly-elected future legislators.

Two more attendees spoke against the local law, including former Enfield resident and one-time town office seeker Amanda Kirchgessner. Kirchgessner expressed much the same position as Dan Klein later would. She recognized Washington’s new reality.

“We do not need to virtue signal through a hyper-localized tokenization process, especially given the retaliatory nature of the current federal administration,” Kirchgessner pleaded to County lawmakers. “We cannot afford to risk losing federal funding or getting involved in an expensive, lengthy lawsuit all because you want to put this into the books,” she maintained.

“I’m not opposed to equitable outcomes,” Kirchgessner qualified. “I am opposed to you putting us in substantial financial risk.”

Dryden’s Mike Lane stood among those legislators opposing CEDO codification. But it was the “straight white guy” insinuations that touched Lane’s nerve and prompted his reply.

“I don’t like what I’m hearing about this debate degenerating into subtle accusations of bias,” Lane commented. “I don’t think that’s the case. I think we’re better than that.”

The CEDO charter debate probably went on far longer than needed. But perhaps because it did, it left several dangling loose ends that never got retied.

First point: Codification’s advocates spoke of the significant support among the Tompkins County workforce for the CEDO position’s preservation. Employee support is important, of course, since its job duties remain primarily inward-focused, advancing equity interests in hiring and promotion. Dan Klein pushed back on any assertion of rank-and-file consensus.

Klein counted only five supportive employee messages. “That’s not a mandate to me,” Klein asserted, adding “And we know, legislators, that we have a bunch of employees that do not like what’s happened with this program. We’ve gotten our emails about that.”

Legislators about the big oval table challenged Klein on that point and maintained they hadn’t gotten those employee protests. The chairman begged off, claiming the emails were confidential and couldn’t be shared publicly.

Second point: When Deanna Carrithers was CEDO, back when the George Floyd-prompted demands for racial justice swept over America and locally, administrators delegated to Carrithers much of the Reimagining Public Safety initiative’s heavy-lifting. But Deanna’s successor, Charlene Holmes, transitioned her priorities and spent nearly two years compiling an “Institutionalizing Equity Report,” a 52-page, densely-worded document that oftentimes read like a doctoral thesis and played to mixed reviews locally.

For public consumption, both Carrithers and Holmes were well-liked. But behind closed doors, it may have been different.

“We’ve had two of them,” legislator Dawson referenced the successive CEDO’s. “One of them I liked very much. The other one I didn’t have much use for,” Dawson conceded, the two-term legislator allowing an ample amount of candor to spill in public view. “And there might have been a dispute between one of our CEDO’s and one of our other highly-placed department heads,” Dawson added. “That’s not the point. There’s always going to be differences of opinion and differences in the way people do a job.”

Dissect Dawson’s comment as you may. We do not know which Diversity Officer Dawson disliked, nor of which “highly-placed department head” was drawn into disagreement. We only know there was trouble and that it involved a personnel dispute of which we were never told.

Amanda Champion will leave the Tompkins County Legislature in a few weeks, retiring after two, four-year terms. In many ways, codifying the Chief Equity Officer could be her way to cement a legacy.

During these past five years, no one has dared—at least, not publicly—to eliminate the Chief Equity and Diversity Officer’s job, even though doing so could save local taxpayers a salary listed for 2025 at $110,593, plus benefits.

What’s more, the CEDO’s elevation to its placement within the county charter seems a relatively recent leap of mental inspiration. Champion told colleagues the idea emerged from her attending a Government Alliance on Race and Equity (GARE) conference a couple months ago.

But whether spontaneous or long-contemplated, the CEDO job is now engrained within the charter. It was put there by majority vote. It could be extracted the same way. Just don’t expect it ever to be pulled.

And what about the danger that the equity officer’s newly-granted institutional prominence could subject Tompkins County to fresh trouble from Pennsylvania Avenue? Deborah Dawson doesn’t plan to worry.

“We’ve already got a big target on her back,” the Lansing Democrat advised skeptics that early-December night. “I just don’t think that adding the CEDO to our charter is going to make the target on our back any bigger than it already is… You know, come and get us.”

###