EMS consultant briefs Tompkins leaders on short-term fixes; long-range vision

by Robert Lynch; October 31, 2025

A quarter-century from now, as one emergency medical services consultant foresees it, a governmentally-subsidized service agency will travel the breadth of Tompkins County, answering rescue calls, picking up patients and taking them to wherever. And when it does, privately-owned Bangs Ambulance will somehow just dry up and blow away.

But that’s then, not now. And the problems of today are what Tompkins County hired consultant Paul Bishop to fix.

For nearly two hours this past Tuesday afternoon—at a meeting that sidelined all other business—Bishop, principal of the Rochester-based Center for Governmental Research (CGR), briefed the Tompkins County Legislature’s Public Safety Committee on what it could do to shore up its emergency medical services (EMS). Persistent problems include longer-than-desirable patient wait times, member depletion of volunteer rescue squads, and the increased deployment of paid municipal ambulance crews to extend mutual aid beyond their own boundaries.

“EMS in Tompkins County is not a cohesive system of care,” Bishop concluded early in his October 28 presentation. He stuck close that day to a 27-slide PowerPoint he’d prepared, one that summarized a more detailed written report most of us have yet to see. “Several distinct service models exist dictated by political boundaries (and) generations of choices by political and agency leaders,” the consultant’s overview asserted.

Put another way, EMS in Tompkins County has evolved—or devolved—into competing camps of providers that rub up against each other and create friction. There’s a profit-driven Bangs Ambulance, which can’t keep up with what it’s tasked to do. There’s an amply-paid Ithaca Fire Department that could do more, but won’t. And there are the not-for profit paid ambulance operators in Dryden, Trumansburg, and to a lesser extent, Groton that find themselves asked too often to bail Bangs out, and to do so at their own fiscal detriment.

In April of last year, Tompkins County inserted a new player into the mix, the Rapid Medical Response (RMR) service. Initially designed and funded to gap-fill for volunteer fire department rescue squads during daytimes on weekdays, RMR’s managers earlier this year sought a much-bolder role, one that involved adding multiple ambulances and quadrupling RMR’s staffing and payroll.

Hesitant about whether a grander RMR was the way to go, the Tompkins County Legislature in June retained Paul Bishop and CGR for $48,000 to offer a more detached perspective. Bishop’s report was due in September, but was late in coming. Tuesday’s Public Safety Committee meeting brought its first airing. While they’d waited for the report, legislators this fall budgeted another year of continued RMR programming, keeping RMR much the way it was when it began and the way it remains.

To an extent, Bishop’s immediate recommendations endorsed the Tompkins County Department of Emergency Response (DoER) proposal for short-term expansion of the RMR program, a plan that would purchase one or two ambulances and secure an all-important “Certificate of Need” from New York State.

But it was Bishop’s “Vision for the Future,” his quarter-century futuristic forecast, that prompted the greatest attention among lawmakers. And it could also eventually generate the toughest scrutiny from those not in the room that day.

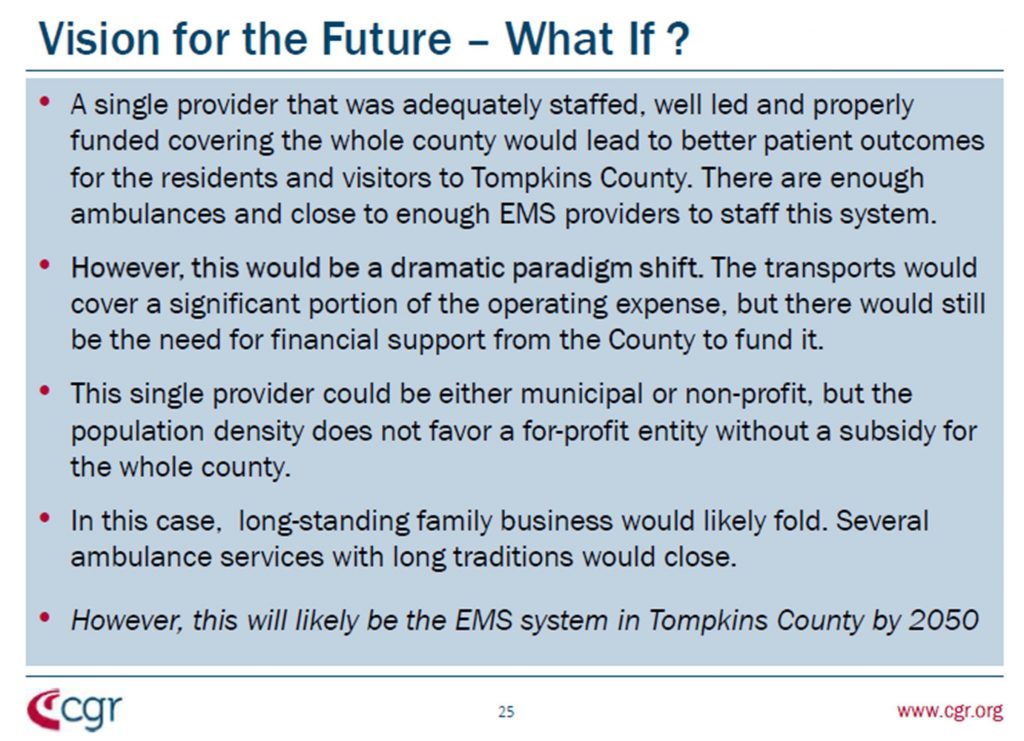

“A single provider that was adequately staffed, well led and properly funded covering the whole county would lead to better patient outcomes for the residents and visitors of Tompkins County,” Bishop’s report boldly concluded. “There are enough ambulances and close to enough EMS providers to staff this system,” the consultant’s PowerPoint “Slide 25,” much-referenced, proclaimed.

”However, this would be a dramatic paradigm shift,” that same slide acknowledged. “The transports would cover a significant portion of the operating expense, but there would still be the need for support from the County to fund it.”

CGR’s 2050 scenario envisions that the single provider would be governmentally-owned or a non-profit agency. But it would not be Bangs.

“If you were to move there,” that is, to a single-provider service, Bishop advised the committee, “Bangs would have a hard time operating,” he said. “If all Bangs was responsible for was covering the City and Town of Ithaca, they could probably do it financially. But we asked them to go or they volunteered to go outside and that really kind of pushes their resources,” Bishop concluded.

“Did Bangs weigh in on your 25-year projection?” Lansing legislator Mike Sigler cautiously asked the consultant at the close of his formal presentation.

“No,” Bishop quietly answered.

Tellingly, unlike during a prior committee review of EMS options in May of this year, no representative from Bangs Ambulance sat in legislative chambers last Tuesday.

And Bangs’ presumed demise would only reflect part of the change.

“Several ambulance services with long-standing traditions, Trumansburg, Dryden, Groton, they would close if you go to a single service,” Bishop predicted within his, over-the-horizon vision of consolidation. “However, this is probably where you’re going to be in 2050,” he said. “You’re going to be at a single agency providing it for the whole county.”

“I can’t speak for Dryden or Groton, but I can speak for Trumansburg,” that village’s mayor, Rordan Hart, told the committee from his virtual perch. “We do not run an ambulance service because we really want to be in the ambulance business; we run an ambulance service because if we didn’t operate there would be no one, including Bangs or anyone to our north, capable of stepping in and picking up the calls that we currently cover.”

CGR’s statistics, presented to the committee, reported that Bangs Ambulance handles about 12,000 calls per year. Dryden Ambulance handles 2,500, roughly one-fifth as many as Bangs does. Trumansburg Ambulance responds about 1,000 times; Groton, 750. Bangs has up to a half-dozen ambulances in service, it was said. Dryden has two. Trumansburg has one.

“What would it cost for a full-blown county ambulance service with 10 to 15 rigs round the clock similar to where we are today?” Groton legislator Lee Shurtleff asked. Shurtleff threw out the estimate of $10-15 Million, with perhaps one-third of that cost recouped through patient insurance reimbursements.

The Groton lawmaker put side-by-side Bishop’s long-range vision and the consultant’s narrower, short-term fix, that is, the one-to-two ambulance RMR expansion.

“But your impact on the taxpayers to run a countywide service is far more than that $2.5 Million that’s quoted here,” Shurtleff said, pointing to the RMR expansion quote.

“You’re talking apples and oranges,” Bishop responded. “That $2.5 Million was for a small apple. And (with county-wide service) we’re talking about a very large orange.”

To defray potential expenses—those that inevitably arise when government owns something—Bishop, instead, envisioned setting up a governmentally-subsidized nonprofit corporation. He nicknamed it “Tompkins County Ambulance, Inc.”

As to the more immediate priorities, the CGR report that Bishop presented pointed Tompkins County down two alternative paths. Each would expand the Rapid Medical Response program under a county-wide Certificate of Need and permit RMR staff to elevate to paramedic-level care, most likely with ambulances in service or at least at the ready.

“This is not to supplant an existing service,” Bishop was quick to qualify concerning his short-term recommendation. “We’re not trying to take any territory or calls, first calls away from anybody here.” Instead, Bishop said, “The goal is to fill gaps, to prevent draining resources from outlying areas, and to be a safety net provider when other sources are depleted.”

The more modest of the short-range options, called the “Bridging Gap Ambulance Service,” would purchase one paramedic ambulance, make it ready 24/7, but deploy it only sparingly. There’d be another paramedic first response vehicle in house and a staffing budget of $1.7 Million. That’s about 2.5 times RMR’s current cost.

The other, more ambitious “Safety Net Ambulance Service” would purchase two ambulances. Only one would provide paramedic-level care. There’d be added staff and a $2.5 Million price tag, 3.6 times RMR’s current budget.

And ambulances come neither cheap nor quickly. Bishop predicted each would incur an additional quarter-Million dollar expense and take 18 months to deliver.

“Ambulances are not inexpensive,” Bishop acknowledged.

If going for that second, pricier option—the one more resembling what DoER staff had proposed last spring—“Dryden and Trumansburg would never have to leave their towns,” Bishop predicted.

Yet just how often would that expensive, taxpayer-paid County ambulance actually leave the station? At least with the “Bridging Gap” option, maybe not often.

“You can choose to run the ambulance only now and then, as long as you’re providing that paramedic service regularly,” Bishop said regarding the less expensive choice.

“How would that work?” Legislature Chair Dan Klein asked, puzzled by the prospect that an expensive new “backfilling” tool might only be deployed twice a month. “That crew is just sitting there on call all the time, or are they in one of our other EMS programs?” Klein inquired.

Bishop said crews would be doing other tasks in other vehicles, although he never convincingly addressed Klein’s question with specificity.

Also left somewhat undefined was exactly how County Government and local municipalities might share any obligations to underwrite the service either short- or long-term. Bishop made clear that current state law forbids counties from establishing county-wide ambulance districts or imposing a county ambulance tax.

“I think that would be a great idea if you could,” Bishop said of countywide ambulance taxation. He urged Tompkins to band together with other counties and lobby Albany lawmakers.

And Paul Bishop’s advice on funding alternatives may have been the least convincing part of CGR’s presentation. The consultant referenced Madison County—no doubt, much different from Tompkins—where a county-wide tax, apparently imposed within the General Fund, gets paid-in disproportionately by towns that lack ambulance service, and paid out to those that have one.

Perhaps an inapt analogy, the consultant equated ambulance funding to underwriting the Sheriff’s road patrol.

Paul Bishop’s report touched on many areas, one or more of which involve tricky turf wars maybe unique to Tompkins County.

There’s the bureaucratic obstacle that may explain why Bangs Ambulance finds itself so overstretched. It’s the refusal by paid Ithaca Fire Department (IFD) staff, contracted to serve the Town of Ithaca as well as the City, to respond to low-level non-emergency calls, like when a frail older adult falls out of her chair or a nursing home patient needs a bed lift. In Enfield, under Fire Chief Jamie Stevens’ recent directive, fire company rescue squads get dispatched to those low-level calls. But in Ithaca, the job is left to Bangs.

“The Ithaca Fire Department has decided that they are only going to respond to the ones that they believe…are life-threatening,” Bishop advised the committee. “And that is still close to half of their calls.”

A second conclusion the CGR study drew is that the 911 Center and local ambulance providers need to triage their medical emergencies. Bishop said the Center right now expects every call deserves a dispatch within a set time, perhaps five minutes. That, he said, should change.

“You don’t need to have an ambulance assigned for someone who has low back pain that they’ve had for a week and now they want to go up to (Cayuga Medical Center),” Bishop observed. “They can wait 20, 30, 40 minutes for an ambulance to show up.”

There’s also a lack of transparency as to how much 911 dispatchers know about Bangs’ operational adequacy or lack thereof, the study found.

“The dispatchers need to know Bangs’ status,” Bishop told the committee. They need to know how many ambulances are available for Bangs. “The other agencies already share,” he said. But with Bangs, “There’s a feeling that it’s proprietary and somewhat dynamic.” CGR was told by Bangs that its status “can change hour-to-hour.”

DoER Director Mike Stitley and Joe Milliman, administrator of the RMR program, each deferred comment October 28 on the CGR report. Bangs’ representatives weren’t there, of course. And municipal representatives of Dryden and Trumansburg proved cautiously supportive. Expect the CGR study to get its next full examination at a meeting of the Tompkins County Council of Governments (TCCOG) December 11.

Paul Bishop predicted that his single-provider countywide ambulance service would come to pass by 2050. Trumansburg’s Rordan Hart believes it may arrive much sooner, maybe by 2035, just a decade from now.

“We’re going to get to a place where the Dryden’s and the Trumansburg’s either can’t, or won’t, or won’t be able to afford providing these services,” Hart told the Public Safety Committee. “How do the small agencies feel about it? I think at worst we believe it’s inevitable and at best we would welcome it simply because of the tax burden to our taxpayers who are providing the service that we already do.”

That “Slide 25,” the one predicting an in-the-future, single-provider service, seems the one most important, Tompkins County Administrator Korsah Akumfi advised committee members that day. “And it is essential that all the partners read that, understand it, and think through the processes and identify what we need to do to solve the problems everybody admits exist,” Akumfi, on the job for less than a year, advised the committee.

Of course, those who must read the report include Bangs Ambulance. And no one likes to read that you’ll be put out of business.

###