by Robert Lynch; August 20, 2025

The stock price of Tompkins County’s 911 dispatching system did not gain value in Enfield Tuesday night.

“There seems to be a real issue with the County,” Enfield Fire Chief Jamie Stevens broached the subject bluntly during the early minutes of the Enfield Board of Fire Commissioners meeting August 19.

And with Chief Stevens’ words, a session whose focus was expected to bring a first peek at next year’s Enfield Fire District budget rewrote its lead headline to one far less fiscal and far more a matter of human injury, if not life-and-death.

Chief Stevens expressed to Commissioners his displeasure with Tompkins County 911 Dispatch, the emergency operations phone center that receives emergency calls, prioritizes them, and then sends out ambulances and volunteer rescue squads according to perceived need. Based on his involvement with an in-home medical emergency the weekend before, the chief concluded the current system is overly-rigid, arbitrarily applied, and disproportionately reliant on what’s read from a book rather than what’s found in the field.

And because of that incident, Jamie Stevens announced his decision.

“I’m now responding to all EMS calls, including ‘Alpha’ calls,” the Fire Chief enounced.

By his orders, Enfield Rescue Squad volunteers will now be sent routinely to those second-to-the-bottom types of emergencies, to medical events to which they hadn’t in recent times been summoned. Up until now, the Rescue Squad had only been activated by the 911 Center on its determination of the next-higher level of emergency, the “Bravo” call, and to call levels more serious.

Before Tuesday’s discussion had ended and the meeting had moved on, not only Stevens, but also Board of Fire Commissioners Chair Greg Stevenson and Enfield Volunteer Fire Company (EVFC) President Dennis Hubbell had all joined in their criticism of the Tompkins County’s 911 Dispatch unit and of the Department of Emergency Response (DOER) that oversees it.

“They do a poor, poor job of it,” Stevenson characterized the 911 Center’s performance. “They don’t listen; they want to argue,” Stevenson complained.

“I have significant concerns about the County being able to manage what they have. I hate to think what it would be like if they had an ambulance service,” Stevenson continued.

Toward that end, the Department of Emergency Response had prepared and submitted to Tompkins County legislators this past May a plan that would vastly expand the County’s Rapid Medical Response (RMR) program, now in its second year of implementation. The expansion would include a limited ambulance operation that would provide basic life support and hospital transport services. Its goal would be to gap-fill an overstretched Bangs Ambulance service as well as ambulance services operated by several municipalities, principally by Dryden and Trumansburg.

The “Enhanced RMR” proposal currently faces a rough governmental ride. DOER’s plan would increase the service’s funding nearly six-fold. Key lawmakers warn that Tompkins County just doesn’t have the money to fund it.

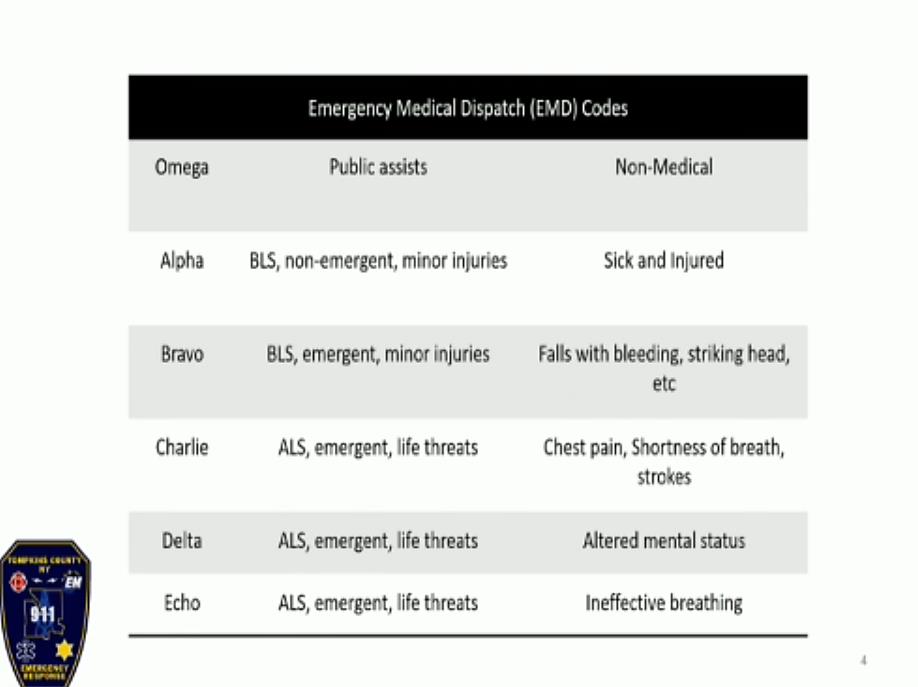

The heart of Tuesday night’s complaints involved the 911 Center’s doggedly-followed “Emergency Medical Dispatch (EMD) Codes,” the ones guiding dispatchers when they assign the severity level of each 911 call. The six categories range from “Omega” calls (non-medical public assistance) through codes “Alpha,” “Bravo,” “Charlie,” “Delta,” and “Echo.” (Note the alphabetical advancement of the final five codes.)

According to a DOER PowerPoint slide shared with county and local lawmakers in October 2023, threats to life would be assigned “Echo” status. The “Alpha” code would be given to “non-emergent, minor injuries,” those where a patient was merely “sick and injured.” By contrast, “Bravo” calls would elevate to “emergent minor injuries,” where someone “falls with bleeding, striking head, etc.,” medical events that may require transport to an emergency room.

The 911 Center’s categorization impacts not only whether a volunteer rescue squad will be activated, but also the sophistication of ambulance equipment and personnel deployed. It also affects whether the ambulance is sent “hot,” with lights flashing ad sirens blaring; or “cold,” proceeding quietly, at normal highway speeds.

The weekend incident that raised Chief Stevens’ ire and prompted his EVFC edict took place at a private residence. It involved a patient with a perceived hip injury whose host called the 911 Center, the caller familiar with the fire service and 911 protocols.

As the Fire Chief and the Commissioners’ Chair pieced details together after Tuesdays meeting had ended, the subject caller had phoned 911 dispatch. The caller had described the patient’s condition. The 911 dispatcher accordingly assigned the “Alpha” severity status. A Bangs Ambulance was sent to the scene, but without lights or sirens… or a paramedic.

As minutes passed, the patient showed increasing signs of injury, an injury likely requiring paramedic-level treatments. The caller phoned back and urged an elevated response.

“We don’t upgrade calls,” the dispatcher firmly told the caller. At that point, the caller enlisted Fire Chief Stevens’ assistance.

“I am the Fire Chief, and I want the call upgraded,” Stevens sternly informed the 911 Center.

At that point, as officials later informed Tuesday’s meeting, the dispatcher backed down, Enfield Rescue was alerted, and a second, better-staffed and equipped Bangs Ambulance was sent.

Last weekend’s botched response wasn’t the first time such an error has occurred, Chief Stevens recalled. One time, he said, “I went on an Alpha call that happened to be a full cardiac arrest.”

Neither Enfield’s rescue squad nor most others respond to the lowest-level “Omega” calls, ones that may not require any medical attention at all. Company President Hubbell equated the typical Omega call to complaining about a “toothache.”

Multiple officials within the Enfield fire service recalled Tuesday that the six-levels of EMD codes were put in place in the early-2000’s at the request of Tim Bangs, President of the private Bangs Ambulance service, Tompkins County’s largest transport agency. And those officials allege Bangs requested the coding protocol for both professional and legal protection.

“The problem is years ago Tim Bangs and his attorney requested the County to do this,” Stevenson told Commissioners.

But EVFC President Hubbell also places blame on the emergency dispatchers themselves and on the arbitrary discretion they employ.

Hubbell remembers that service as a 911 dispatcher used to require one’s holding an EMT (Emergency Medical Technician) certification. No longer. A dispatcher qualifies by having acquired a largely textbook- and lecture-based Emergency Medical Dispatch certification. One completes a course at the Fire Academy in Montour Falls, takes the test, and then starts answering calls.

“You do well on your test, but you have no real fire or EMS service experience,” Hubbell complained. “It’s like having a truck driver who doesn’t have a license.”

The company president Tuesday endorsed the heightened local response protocols that Chief Stevens imposed effective with Tuesday’s meeting. Yet Hubbell concedes those rules have a downside. They will summon volunteers more frequently and place increased strain upon each member’s time and commitment.

“I agree with what we’re doing,” Hubbell stated. “It’s going to cover our butt.”

At the same time as the Board of Fire Commissioners was addressing dispatching, County Administrator Korsah Akumfi in downtown Ithaca was briefing the Tompkins County Legislature on his progress in refining next year’s requested Tompkins County Budget and in narrowing an earlier-forecast $11 Million budget deficit.

As it stood that night, Akumfi still forecast a $4 Million to $4.5 Million budget shortfall. Yet among the programs retained in his draft calculations, Akumfi said, was “the Rapid Medical Response service, as is.”

Those final two words hold meaning. If they are taken at face value, Akumfi’s budget, to be finalized for legislators next week and shared with the public after Labor Day, would not include the more expensive RMR enhancements that DOER has strongly lobbied for. DOER’s initiative, if adopted, would boost the RMR annual budget from its present $544.828 to more than $3 Million.

County-run Rapid Medical Response currently operates only during daytime hours and only on weekdays. The enhancements the Department of Emergency Response seeks would expand the service to nights and weekends. And though its rules stand slightly at odds with the dispatching codes, Enfield fire officials report that the RMR vehicles, staffed by EMT’s do, indeed, answer Alpha-level calls. And they respond using lights and sirens.

Had enhanced RMR been operating on the night of the Enfield Fire Chief’s publicized emergency, RMR might have then responded. Still, its lone after-hours van might have been deployed elsewhere in the county that night, rendering its availability meaningless. And the RMR unit may have had only an EMT on board, not a more-skilled paramedic, a professional authorized to administer a higher level of care and provide more specific medications.

And any new ambulances requested to bolster RMR’s stature would only provide basic life support and hospital transport, not advanced life support, were it needed.

And, of course, the dispatch system would remain the chain’s weakest link. Heightened emergency response is only as effective as the dispatcher who requests it.

Enfield is not the first local fire company to expand its responses into Alpha-level emergencies. Most of Tompkins County’s fire companies have already done so, Chief Stevens stated after the meeting. Enfield and Lansing, he said, were the final holdouts to expand into this (supposedly) less-serious status of medical events, less-serious, that is, if you can believe that the 911 dispatcher is correct—which, of course, has become the problem.

The Board of Fire Commissioners came close Tuesday to formally endorsing Chief Stevens’ expanded activation rules through passing a resolution. The board stopped short of doing so at the last minute, concluding that a unanimous, informal expression of consensus stood sufficient.

“It’s a shame we have to address our policies to make up for the poor performance on the other end,” Chairman Stevenson remarked as the board ended its discussion of 911 Dispatch and moved on to other business.

“Is the County ambulance the right decision?” Stevens asked fire commissioners, the fire chief implying that such a service would not be. Can life-and-death decisions “be made by one phone call,” Stevens asked?

But for Enfield, the Fire Chief’s weekend call may have made a long-term difference. Enfield EMT’s will now be called out more often. The community’s rescue squad will have an added presence. Expect the fire station door to open more frequently.

And yes, expect Enfield fire officials to urge a change in what may have become an imperfect Emergency Medical Dispatch coding system, not to mention the way that system’s getting applied.

###