Reporting and analysis by Robert Lynch; July 9, 2024

How does a $24 an hour Tompkins County Minimum Wage strike you?

It’s not the law yet. It may never be. Albany may not allow it. But a committee of the Tompkins County Legislature, all Democrats, took initial action Monday toward enacting a local law that would set our county apart from the rest of Upstate New York and establish a county-wide Minimum Wage set at some level higher than the $15 an hour that state law now mandates. Action came at the prodding of workers’ rights groups, Cornell’s service employees’ union and the most liberal of the Legislature’s 14 members.

“This Resolution is not the policy itself; it is not the law itself,” that legislative sponsor, Ithaca’s Veronica Pillar, qualified to her colleagues Monday, “but it is a necessary step, because to craft something that works requires investment of time, both community engagement and legal and other types of research on the back end.”

With one member—an important member—absent, the County Legislature’s Housing and Economic Development Committee supported adoption of Pillar’s proposal, four votes to nothing. The Resolution encountered no pushback whatsoever. Had the committee’s fifth member, Republican Mike Sigler, attended, no doubt the afternoon’s debate would have turned far different.

Heavy on aspirational platitudes, yet lean on substantive impact, Pillar’s initiative falls short of its stated title: “Implementation of Higher County-Wide Minimum Wage with Local Law Establishment.” The Resolution’s text fails to state what a Tompkins County stand-alone minimum wage might be, when it would take effect, how it would be calculated, or most importantly, who’d enforce it.

As Pillar worded the Resolution, it “directs the County Attorney, County Administrator, and other county staff as needed to collaborate with community stakeholders to develop an effective and sustainable minimum wage policy and draft a local law outlining the specifics of the policy, including the calculation methodology, annual adjustment mechanism, enforcement provisions, and any exemptions or special considerations deemed necessary.”

Yes, that’s quite a mouthful of wiggle-words.

The recommendation could go before the full County Legislature for a final vote as soon as July 16th.

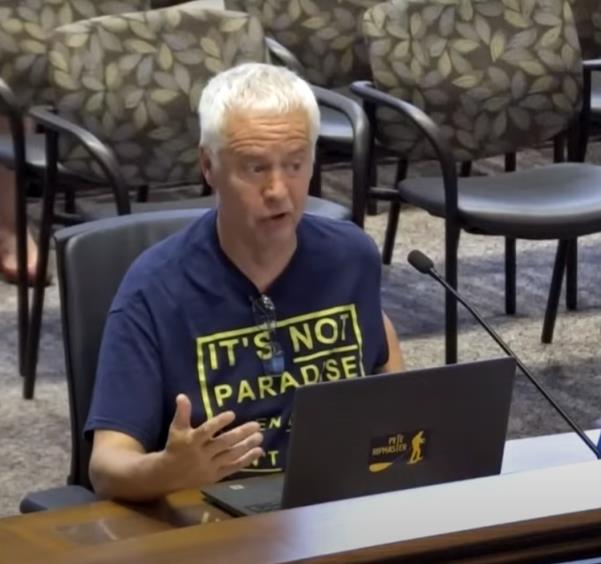

“The minimum income to survive in Tompkins County is considerably higher that (in) many counties in Upstate New York,” Pete Myers, Director of the Tompkins County Workers’ Center, told the committee. “So the cost of living here is out of control, and we don’t need to belabor that point.”

Monday’s committee discussions and the advocacy that preceded it muddled the important distinction between a governmentally- mandated “minimum wage” and the “living wage” that advocates argue should constitute the true floor of compensation. A Living Wage provides a paycheck that covers the necessities of life, at least as some might calculate them.

“It’s kinda’ looking like the Minimum Wage (actually, the Living Wage) will increase to around $24 an hour range in November of this year,” Myers said with a wince, his prediction a shocking revelation in itself. “And potentially we’re looking at a $24 an hour range right now,” Myers cautioned, “and that would be the cost of housing that’s really raising that more than anything.”

Locals traditionally rely on the local Living Wage calculations that Alternatives Federal Credit Union makes annually. Critics have faulted the Alternatives methodology as being too worker-generous. Yet no one so far has chosen a different benchmark.

Alternatives last calculated the Tompkins County “Living Wage” at $18.45 per hour last November. The Living Wage stood at $16.61 the year before.

To people like Myers, the “Living Wage” should stand as the floor. So should Tompkins County withstand any legal challenge and enact its stand-alone Minimum Wage, expect activists to set $24 as their goal, if not a higher rate. $24 an hour would stand 60 per cent above New York’s current wage requirement for Upstate. (New York’s Upstate Minimum will rise to $15.50 next January, and then to $16 per hour in 2026.)

The Workers’ Center Director brought allies with him to the committee meeting. As many as four of the five he invited were either leaders of Cornell University’s principal employees union, the United Auto Workers, or UAW union officers. Some 1,200 Cornell service and maintenance workers are covered by the union local. Contract negotiations come up this fall. That fact was not lost during Monday’s meeting. Indeed, Cornell workers’ grievances found themselves inextricably intertwined with the committee’s wider policy deliberations.

Christine Johnson, Local 2300 UAW President, complained that her Cornell job pays only $28.17 an hour, and yet she’s forced to drive 55 minutes to get to work. (Note than Johnson’s wage is almost twice New York’s current minimum.) She said her partner earns just over $20 an hour at Cornell Dining.

“We struggle financially, and do without a lot of extras,” Johnson said. Speaking for those she represents, Johnson added, “We need a reset on what is just, fair and good for people who work full-time jobs, pay taxes, and also vote.”

“People are not asking for a lot, they’re just asking to be able to live,” Lonnie Everett, the UAW’s Regional Service Representative, told the committee, “because I watch a lot of folks who are not able to live, and there are folks who are all right with that.”

In line with Everett’s remark, and at Pete Myer’s request, the committee played and streamed to the public—somewhat reluctantly—a four-minute, UAW-produced, Cornell-critical video that stopped nothing short of “Ezra-bashing.” At least one former Tompkins County official has termed the video inappropriate and biased and argues it never should have been aired before the committee.

Michael Demo said he works at an (unidentified) local hardware store. He also joined Pete Myers at the meeting. “It takes a lot of time and energy when you’re trying to get by on such low wages as we have right now,” Demo complained. “People have much better things to be doing with their time,” he said.

Demo mentioned a friend, an “accomplished crochet artist” who “would like to sell more of her work on the side.” Another would like more time to spend with her children.

Of course, Demo never brought up the fact that if his hardware store were to close because a higher minimum wage made it impossible to make payroll, his own less-than-desirable job would disappear, and his pay would drop to zero. But statements like that never get raised by people like him at events like these.

Yes, the committee meeting demanded Mike Sigler’s input.

But there’s another argument, a legal one; a position that makes all that transpired that day about a local minimum wage perhaps little more than academic. State law may not allow Tompkins County the freedom it seeks.

There’s a pesky little case called “Wholesale Laundry v. City of New York.” Tompkins County Attorney Maury Josephson told the committee the case was litigated in the 1960’s and remains Good Law today, reaffirmed as recently as 2006. The Court of Appeals had held that New York State pre-empts localities from setting their own, higher, minimum wages. State Government reserves the power all to itself.

“If adopting a local Minimum Wage, keep in mind that that effort would involve, if challenged… an effort to overturn long-standing precedent,” Josephson warned. Tompkins County, he said, “would be sort of at the vanguard of obtaining this reversal, which is an uncertain prospect.” Winning such a case, Josephson told legislators, “would involve a substantial expenditure of effort,” both by his office and by County Administration.

Nevertheless, expect some lawmakers, particularly liberal Democrats, to kick the tires of a local minimum wage, if for no other reason than to prove their good intentions.

“It is my duty to help to bring this forward,” Ulysses-Enfield legislator Anne Koreman remarked after seconding Pillar’s initiative. “People deserve to have that right to be able to have a job that pays for your basic expenses and working 40 hours a week to do that and not to have to work two or three jobs.”

Committee member Travis Brooks likes a stand-alone Minimum Wage as well, yet would first want to know “is this something that can be done before we spend a lot of time figuring out what that looks like.”

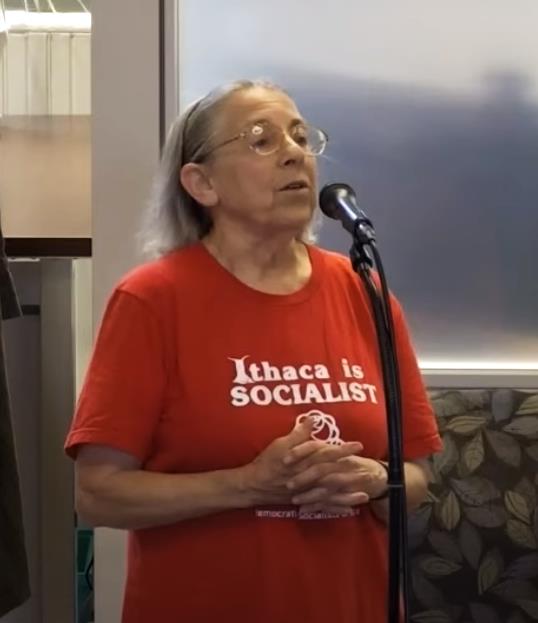

“This is not a partisan issue, it’s an issue of justice; of being fair to everybody,” former Ithaca Town Supervisor Herb Engman said at the start of the meeting.

Committee Chair Greg Mezey stressed the tentative nature of what his group that day was passing forth to the full Legislature—and then, maybe on to the experts.

“This is really just sort of hitting the ball off the tee, and this is not knowing what course we’re playing, what the par is, or what anything is ahead of us,” Mezey reminded everyone.

Without a contrary opinion, a committee of legislators and their friendly allies in the gallery can say and do just about anything. And that’s what happened in legislative chambers on Monday. As said, the moment needed Mike Sigler.

###