Planners, Town Board could have bridled Breezy Meadows, but didn’t

Analysis and Commentary by Councilperson Robert Lynch, June 5, 2023

“But, you know, you still have to give people rights to do what they want with the land they own,”

Enfield Planning Board Chair Dan Walker; May 10, 2023

Woulda, Coulda; Shoulda… but clearly didn’t. And frankly, now it’s too late.

That’s this writer and Councilperson’s view when it comes to Enfield’s approach to a proposed 33-lot, Podunk-to-Halseyville Road subdivision that virtually nobody in this town wants, but that now propels itself toward fast-track approval, with Enfield’s Planning Board—and now the Town Board’s majority—either refusing to tap the procedural brakes to slow the pace of supposed progress or else pleading the weakened excuse that regulations leave them helpless to act.

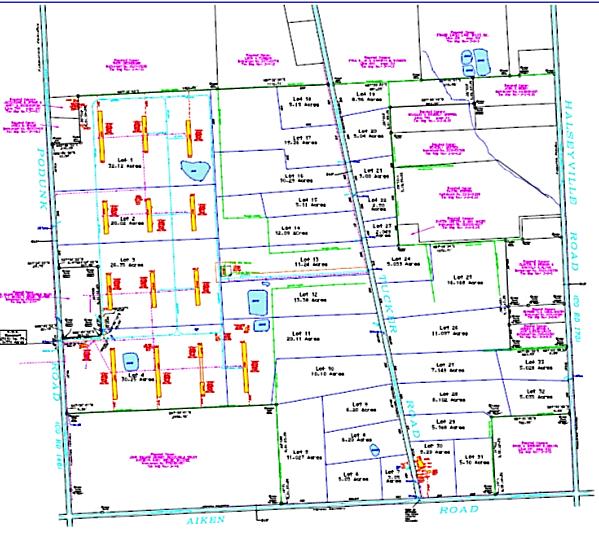

Expect the Town Planning Board this Wednesday (June 7th) to approve the “Breezy Meadows Farm” subdivision, New York Land and Lakes Development’s ambitious carving of Enfield’s rural landscape. Breezy Meadows has become Enfield’s most hotly-debated commercial land-grab controversy since the Black Oak Wind Farm fiasco of a decade ago. Land and Lakes would chop the former John William Kenney farm—a now-overgrown, 337-acre weed patch that includes its more than one dozen, sprawling, decaying former Babcock chicken barns— into building lots of varying sizes ranging from three to 32 acres. Expect those lots to be snapped up over time by transplants from Ithaca, or maybe even New York City.

One can envision many a lot as being just the right size for the hobby farmer. But the likely carving up of one-time cornfields also brings to neighbors who border the sprawling subdivision anxious distress. Many of those neighbors have bedrock wells producing marginal yields at best. Those wells already draw forth too little of what Mother Nature offers. Thirty-three new homes would likely bring new wells of an equal number. And as I cautioned my Town Board colleagues and Enfield’s Planning Board Chair May 10th in my passionate, yet failed attempt to steer Breezy Meadows’ review into a more cautious lane, “There’s only so much water to go around.”

Earlier, at a well-attended—and decidedly critical—Public Hearing April 5th, and again at the Planning Board’s session a month later, I’d called upon Town planners to require Land and Lakes to prepare a detailed Environmental Impact Statement for its subdivision. I also wanted the Oneonta-based developer to underwrite a professional hydrological study to assure Breezy Meadows’ neighbors that new wells would not draw away so much water that they’d endanger neighborhood supplies. Planners ignored my suggestions. Instead, they adopted the semantically-confusing, yet developer-friendly, “negative determination of environmental significance.” And they declined to demand the Environmental Impact Statement. Breezy Meadows won.

The Planning Board’s unanimous vote gave Breezy Meadows its most significant procedural victory. What will likely follow June 7th only grants finality. All the regulatory grunt work came in May.

“The Planning Board did not accept either one of those recommendations,” I counseled my Town Board colleagues May 10th, as Planning Board Chair Dan Walker concluded his customarily routine and perfunctory monthly report to our Board. “And I thought that maybe it would be an opportunity here for this Town Board to discuss whether they think that was the proper decision,” I added.

“The Planning Board has the authority under current law,” I acknowledged. “We’re not disputing the Planning Board’s authority here. We’re just saying that, I think, personally, as one Councilperson, that it was the wrong decision to make.”

My request for Town Board pushback got no takers. Nonetheless, it brought with it another form of good. It generated a more than 30-minute, triangulated and focused conversation over whether the Planning Board’s decision was correct. And even if the Planning Board had erred, participants pondered, it raised the question of whether the Town Board or its Planning Board partner holds the legal license to demand from Land and Lakes a more stringent level of review.

“I think that the Planning Board is going by the regulations that they have in their land use regulations,” Town Supervisor Stephanie Redmond said that night in Walker’s defense. “So they’re following that to the tee,” she added. “And if we want to change that, we need to change that substantively within our Site Plan Review laws or our Subdivision Regulations.”

Redmond’s key argument, one she leaned on repeatedly, was that regardless of Breezy Meadows’ worth or danger, Land and Lakes had found a snug regulatory crack to crawl within. The Supervisor maintained that without tighter site plan review—the Supervisor mentioned town-wide zoning at one point—that a hydrological study could not be demanded now because Enfield’s Subdivision Regulations and its Site Plan Review Law simply make no provision for it.

I, Councilperson Robert Lynch, by contrast, pushed the envelope. I noted that a key question (Question 4-b) on Part 2 of the State-mandated Full Environmental Assessment (SEQR) form directed the Planning Board, the project’s lead agency in SEQR review, to state whether the “water supply demand from the proposed action may exceed (a) safe and sustainable withdrawal capacity rate of the local supply or aquifer.” The Planning Board concluded that any impact on the water table would be minimal or nonexistent. But the form demanded the Board cite a specific source to support its conclusion. Finding a credible citation proved tough for Town planners.

A valid source, I argued, would be the hydrological study I had requested. And without that valid source, I insisted, the Planning Board would have lacked a basis for its dismissive conclusion. If they’d found otherwise—that wells might be endangered—then it could have triggered calls for an Environmental Impact Statement from the developer.

Planning Board member Mike Carpenter had “agonized” over the source citation, I reminded Chairman Walker on Town Board meeting night. And although Land and Lakes had presented Walker’s Board in late-April a self-compiled “Well Water Study,” I described the developer’s submission as a “very cursory, generalized, and non-particularized water study,” one based on Town-wide water logs and “anecdotal” evidence.

“They sought information from three well drillers,” I told Walker at the Town Board meeting. “Two of well drillers had (said), ‘Well, I don’t think it will be a problem.’ And the third well driller didn’t even return their phone calls. So I don’t think that’s a sufficient water study,” I said.

“So it was generous of Land and Lakes to even do that level of study into the water conditions there,” Redmond countered. “Because as far as our Site Plan Review laws go, and our Subdivision Regulations go, they’re not held to do anything like that.”

The Supervisor continued, “Even if the study came back and said every house around there will lose all of their water, they still—it’s not part of our Subdivision Regulations that it would impact the subdivision there…. They can’t just arbitrarily enforce regulations that do not exist. ”

Supervisor Redmond and I did most of the talking during the Town Board’s 30-plus minute go-around that Wednesday night. Councilperson Jude Lemke spoke only sparingly. Cassandra Hinkle spoke to the matter not at all. Councilperson James Ricks did not attend.

The rhetorical triangulation repeatedly retreaded old ground. Redmond latched onto the Subdivision Regulations’ alleged inadequacy. I maintained that the Planning Board could have protruded its neck further to address water-supply impact, thereby fulfilling its mandated role. And Dan Walker, whose opinions most firmly guided the Planning Board’s Breezy Meadows review, defended the Board’s lack of further inquiry because, as he saw it, the 33 new lots would be so widely spaced that one purchaser’s well would not deplete anyone else’s well, either within or outside of the development tract.

“They’re not going to draw down the aquifer for a residential use,” Walker insisted. Still, moments later, the Board Chair, who lives very near the Breezy Meadows site, cautiously acknowledged, “And it’s typical in that area that … there’s water yield problems.”

Walker assured the Town Board that Land and Lakes plans to guarantee to buyers the buildability on any lot it sells, “which means they have to have a water supply,” he said. “That’s in their contract. That’s what they told me, anyhow.”

Nonetheless, Walker followed his statement with a wise nugget of common sense: “If you’re worried about a water supply when you’re building a house, you probably ought to have the well drilled before you build the house, just in case.”

Of course, those who drilled—and then built—on adjacent parcels decades ago can find scant solace in Walker’s admonition. They’ve already bought into the risk. They have houses—and wells.

But the May 10th debate continued to cycle. Dan Walker deflected the need to worry. Supervisor Redmond deferred tightened oversight to another day; a day when stronger laws stand at the ready. And I, for my part, painted a worst-case scenario of what may loom for those who live nearby.

“What happens—what happens when these 33 lots get built, the wells get drilled, and the people outside the development area, their wells go dry?” I asked. “What will we as a Town Board do about that?”

Supervisor Redmond offered a less-than-comforting answer.

“So currently, under New York State law and Town law, they would get something like a ‘Water Buffalo’ to come and fill a tank,” Redmond said. “That’s what usually happens. If we want something different, we need to build it into our regulations. We need to build those into our Town law.”

“I would suggest that what we’ll have to do is we’ll have to bite the bullet and we’ll have to have a water district,” I rebutted. “And we’ll have to bring in water from Ithaca or Trumansburg. And that’s going to be something that’s going to be a big, heavy lift for this Town.”

The nearest public water source for Enfield is the huge, blue standpipe at Iradell and Van Dorn Roads, just over the town line in Ulysses. Bolton Point sources the water that’s there. Ulysses purchases it from the Town of Ithaca. The water supply’s plentiful. But it would take miles of pipe to bring the water to Breezy Meadows’ neighborhood. Sources peg construction costs at a Million Dollars a mile.

As for public water, “We’ll probably have to do it at some point anyway,” Supervisor Redmond opined. “We are going to be facing development in Enfield. We are going to be facing development in Enfield.” She repeated her words for emphasis.

But long range prescriptions aside, I was seeking that night short-term remedies for the years—maybe the decades—before public water ever comes Breezy Meadows’ way.

I had scripted a Town Board Resolution for possible submission. As I sometimes do, I kept its text aside, not sharing it before the meeting. While it acknowledged the Planning Board’s “direct authority” and its “legal jurisdiction” over Breezy Meadows, my Resolution would have called upon the Planning Board to condition its subdivision approval upon the developer’s submission of “a professionally-prepared, sufficiently-rigorous hydrological study,” a study acceptable to the Planning Board, “to document the absence of significant adverse impact on the water well resources to those persons residing within reasonable proximity” of the development area.

My Resolution would also have urged the Planning Board to require Land and Lakes to negotiate a Road Use Agreement with the Town so as to underwrite the likely need to upgrade Tucker Road, now lightly-traveled, but likely to see increased traffic once more than a score of new homes line it. My recommendation thereby addressed yet a second concern raised by Breezy Meadows’ critics.

But that Resolution stayed in its folder all night. I did acknowledge its existence, but did nothing more. Reading the room, I realized that no other Town Board member would have supported it.

“Well, I don’t think the Board is prepared to override the Planning Board at this point on this issue,” Councilperson Jude Lemke remarked, Lemke offering one of her few comments in the evening’s Breezy Meadows go-around.

“I think that there was an opportunity, an opportunity that was probably lost by the Planning Board,” I counseled the Town Board that night. “That because of the need; and the potential to draw down the water supply of people in that area, that they could have required the developer to do a hydrological study as a condition to getting its site plan approval. I think they could.” I said.

I had more to tell the Town Board. I’d noted that commenters at the April third Public Hearing had mentioned Tucker Road’s potential need for paving. They’d also referenced the threatened removal of hundreds of acres of farmland potentially available to anyone with a tractor and a plow. Marguerite Wells, a Hayts Road sheep farmer whose farm rests only a fraction of a mile from Breezy Meadows, had raised that argument most passionately at the April Hearing.

“It kind of makes a farce of the Public Hearing process,” I told Chairman Walker, “because the expressions, the opinions expressed at the Public Hearing really were not regarded highly by the Planning Board.”

“Yes, they were,” Walker responded. He strongly disagreed with my assessment. “We do take those comments into our discussions, and we do take them seriously.”

Nonetheless, Dan Walker closed what likely became the Enfield Town Board’s last extended talk about Breezy Meadows’ with a telling statement as to how he and his Planning Board view the controversial subdivision they will soon approve; and perhaps also how they weigh other projects before them.

“But, you know, you still have to give people rights to do what they want with the land they own,” Walker said. “That’s where we have to evaluate everything.”

It’s tempting for some observers to label our May 10th triangulated Breezy Meadows exchange as “Lynch’s Last Stand.” Please don’t do that. Because this controversy has many chapters yet to be written; many concerns still to be addressed. Before those new chapters become part of Enfield’s future challenges for those of you living in Breezy Meadows’ shadow, keep track of the water tanks you fill and the pumps you run. And here’s hoping you don’t need that “Water Buffalo” to come visit your home anytime soon.

###