To my readers: Too edgy an essay, some may say. Don’t criticize Cuomo; he’s kept us safe, others will complain. But I’ve never hidden from you my belief, a lesson drawn from life, a principle by which I attempt to live, that whether serving in Enfield government or in meeting any other challenge, a successful journey depends as much upon the path you take and the rules you follow as it does upon the destination you reach. What I write here I write from the heart. Please understand what drives my thoughts. Please read my words with an open mind. / Bob

June 27, 2020

“Thank you to all the people who send me letters and tweets, and wave on the street, or give a thumbs up. I can’t express how much it means to me. Your energy keeps me going, and your smiles lighten my soul, and I thank you. To the 59 million viewers who shared in these daily briefings, thank you. Thank you for giving me the benefit of the doubt, thank you for believing in me and giving me support. Good Lord knows I needed it, and don’t worry, I’m not going anywhere….”

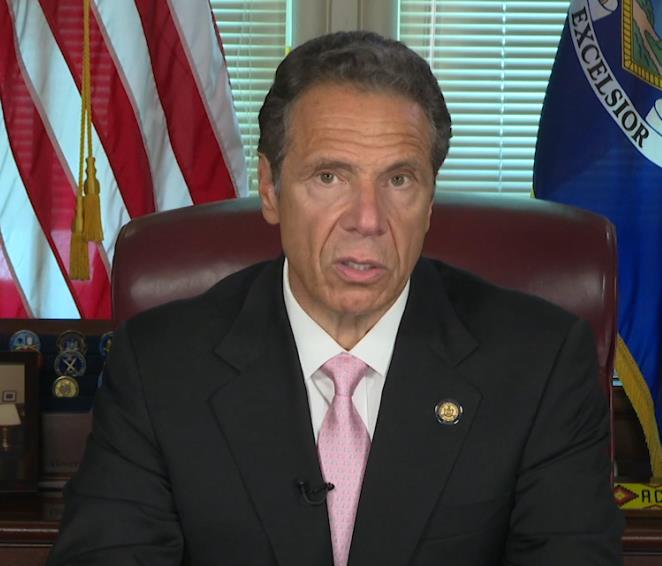

New York Governor Andrew M. Cuomo, at his final daily COVID briefing; June 19, 2020

Governor Andrew Cuomo needs an intervention. Addicts always do. The intervention won’t help him much. But it will surely restore the rest of us. Andrew Cuomo is addicted to power. And with every taste of that intoxicating elixir, he demands more. We, the citizens of New York, have become his enablers. We turn a blind eye. We accept our Governor’s betrayal of Democracy in exchange for the good work he may have done. We’ve become as much of the problem as he has. We must step in, speak up, and act. We must shout Last Call and then help our self-congratulating, power-obsessed, too-drunk-to-drive King Andrew stumble back home. It’s time; indeed, it’s overdue. We must save ourselves from ourselves, and also from him. We must find someone better, a chief executive more respectful of our liberty and the Rule of Law, to lead the Empire State in 2022.

It could be a liberal. It could be a conservative. It might be some obscure Councilperson from Horseheads or Wappinger’s Falls. Just let it be someone in our great State of nearly 20 million who comprehends the limits of ordered democracy better than does our incumbent. He need not be too smart. She need not be a master at political chess. He or she need not be our Savior. The person we elect need only understand one bedrock truth: A benevolent dictator remains, despite all else achieved, a dictator still.

Who gave Andrew Cuomo the power to declare a state holiday? I guess he did. On June 17th, in a transparent attempt to placate a key constituency and pluck a fig leaf from the tree of political correctness, Governor Cuomo, by executive order, declared Juneteenth, just two days later, a state employee holiday. I thought we had legislatures to make decisions like that. I guess no longer.

Our governor claimed authority to send state workers home (or into the stores), he says, “by virtue of the Constitution of the State of New York, specifically Article IV, section one, and the laws of the state of New York.” Quite obviously, Cuomo assumed none of us would bother to read that enabling clause. I did. Article IV, Section one of our Constitution states:

“The executive power shall be vested in the governor, who shall hold office for four years…” [The section’s remaining words describe how the governor and his lieutenant will be elected].

Quite obviously to Andrew Cuomo, “executive power” means absolute power. And this singular presumption explains everything else that’s transpired—how Empire State democracy has so run amok—these recent months.

Mind you, I have no problem with our State declaring another holiday, one to honor the heritage of a long-defiled and still-mistreated segment of our society. But a normal legislative process exists. A governor proposes; the legislature disposes. One House adopts; the other concurs; the governor signs. Only then do the banks, the schools, and the DMV lock their doors on June 19th. That’s how a “republican form of government”—a constitutional phrase—is supposed to work. Not here. No longer.

Earlier, on March seventh, Andrew Cuomo declared by executive order a statewide disaster emergency because of COVID-19. No complaint from me. A governor may declare emergencies to address any crisis and carry orders forward for any sensible time. A flood, a riot, or a pandemic dictates immediate response and with the speed and dispatch reserved to an executive. But as he battles the enemy of the instant, a governor should also exhale. He should stop, think, propose, and negotiate. He, and we, should ask ourselves whether and how New York’s 212 elected legislators should intervene. What meaningful, timely, and procedurally appropriate measures should they enact? What emergency limits must they impose on our individual liberty, yet do so with the constitutional soundness New York’s founders intended.

Andrew Cuomo attempts none of that. Instead, he has stretched state statutes like a bungee cord. Flowing from that single March seventh declaration, Cuomo has penned 45 (and counting) multi-faceted supplementary edicts. Well-intentioned? Yes. Effective? You decide. But all of them imposed with the stroke of an executive’s pen, not a legislature’s roll call.

Why must we wear a mask in public when not socially-distanced? Look no farther than Executive Order 202.17. Why cannot our families or friends gather in “any size for any reason?” See Executive Order 202.10. It took still later executive decrees to inch those crowd sizes upward to ten, 25, and now 50. We have padlocked our schools, postponed our primaries, and mothballed a state’s whole economy just on our Governor’s say-so. Necessary measures, perhaps. But why not do it the right way, the democratic way?

Perhaps for Cuomo, grinding legislative sausage makes too much mess. It consumes precious time and leaves his hands too dirty. Yet why can our Enfield Town Board, upon our Supervisor’s sound urging, take action in a matter of minutes but the State Legislature cannot? Quite obviously, to the Governor, expediency does not dictate his choice. Power does. Better he go before the klieg lights each Noon, utter divine inspiration, aggrandize his power, and take all the credit. For him, for a while, it has succeeded. By late-April, polls placed Andrew Cuomo’s job approval at near 80 per cent. (It’s since dropped.)

But please, don’t look too closely. Despite all those orders, critics now fault Cuomo for failing to foresee, or prevent, our State’s deadliest blunder. Not until May 10th (E.O. 202.30) did Cuomo reverse a March State Health Department directive that had barred nursing homes from testing incoming patients for COVID-19. The sickly hospital discharges had sprayed the rehab halls with germs. That one wrong-headed misstep, and Cuomo’s delayed response to it, may explain why New York’s COVID death count became the nation’s worst.

Each of our Governor’s many-layered COVID commands claims its authority in Section 29-a of Article 2-B of New York’s Executive Law. Again, quite astutely, Cuomo supposes most of us will no more read state statutes than we will cell phone contracts. So please, let me, your legal geek, assume the chore.

First, the name. Section 29-a tags its title as “Suspension of laws.” It talks of “suspension,” not “creation.” The text immediately follows:

“Subject to the state constitution, the federal constitution and federal statutes and regulations, the governor may by executive order temporarily suspend any statute, local law, ordinance, or orders, rules or regulations, or parts thereof, of any agency during a state disaster emergency, if compliance with such provisions would prevent, hinder, or delay action necessary to cope with the disaster or if necessary to assist or aid in coping with such disaster.”

The second sentence may be the clincher:

“The governor, by executive order, may issue any directive during a state disaster emergency declared in the following instances: [A laundry list of applicable disasters follows. They include “epidemic.” The paragraph continues:] Any such directive must be necessary to cope with the disaster and may provide for procedures reasonably necessary to enforce such directive…”

Oh, at times like these, I wish I were a judge. And any jurist schooled in legal textualism—Antonin Scalia, we need you—would spot the problem. The paragraph, by the plain meaning of its title and the inferences one easily draws, establishes the parameters for, and the guardrails limiting, executive power in suspending existing laws. It does not necessarily permit writing new ones.

Indeed, how broad a set of shoulders does “may issue any directive” have? And most important, do any legal shackles bind that second sentence to the first? If, indeed, as the Governor assumes, the second sentence stands free from the one preceding it, should not have the Executive Law’s draftsmen (they probably were all men) have titled this paragraph differently? Might better they have named it, “Suspension of laws and other emergency powers”? Yes, to opine like Scalia. He’d have made ground round of our governor.

But perhaps a finer jurist than Scalia was Robert Jackson. When law students at Cornell and elsewhere seek the constitutional bounds of executive power, they invariably travel through Youngstown (the steel mill case, not the city.) In Youngstown Sheet and Tube Co. v. Sawyer, 343 U.S. 579 (1952), Justice Jackson offered an eloquent, insightful concurrence to adorn an otherwise gull-gray majority opinion.

The facts were straightforward. In the midst of the Korean War—and a steelworkers’ strike—President Truman had nationalized the mills. For pretext, Truman used national security. More likely, he sought to advantage labor. The steel mills fought back. The Supreme Court then pushed back, holding that Truman had violated the Constitution. “The Founders of this nation entrusted the lawmaking power to the Congress in both good times and bad times,” the majority wrote. Justice Jackson took it from there.

To divine the Constitution as Robert Jackson did is not to read icy words penned to parchment, but to fathom the framers’ machine of democracy; one grounded on thoughts placed firmly in mind and passions held hotly in heart. Jackson’s Constitution was a purpose-driven document, founded on function, where executive power ebbed and flowed, gauged by how many of those holding legislative clout took the President’s side. Justice Jackson:

“When the President acts pursuant to an express or implied authorization of Congress, his authority is at its maximum, for it includes all that he possesses in his own right plus all that Congress can delegate….” But “When the President acts in absence of either a congressional grant or denial of authority, he can only rely upon his own independent powers….”

To abbreviate: The more numerous your allies and the more loyal they become, the greater your executive might. But what Justice Jackson wrote next might still spare Governor Cuomo, at least a bit, at least for the moment:

“[B]ut there is a zone of twilight in which he and Congress may have concurrent authority, or in which its distribution is uncertain. Therefore, congressional inertia, indifference or quiescence may sometimes, at least as a practical matter, enable, if not invite, measures on independent presidential responsibility.”

In such a zone semantically of Rod Serling’s creation, when legislative leadership ebbs to its lowest, then, Jackson opined, “[A]ny actual test of power is likely to depend on the imperatives of events and contemporary imponderables rather than on abstract theories of law.” In street speak: Think pandemic. Think fear. Think this spring.

To sum up, according to Youngstown’s most remembered jurist, when legislators in a crisis head for the hills (or vacate their chambers in Albany to seek shelter under the bed), an emboldened Governor may step onto toes and leverage his sliver of concurrent power to his advantage. And surely Cuomo has done just that. Remember, however, that Justice Jackson still found President Truman had lacked the license to do what he’d done. In parting, Justice Jackson left us with this:

“We may say that power to legislate for emergencies belongs in the hands of Congress, but only Congress itself can prevent power from slipping through its fingers.”

Wise advice for today. Should we fault the New York Legislature, a diverse chorus of more than 200, for lazily letting its own power atrophy, for enabling King Cuomo to expand his authority as much as he has? Or should we instead blame ourselves for tolerating this quiescence? The Governor holds like-party majorities in both legislative Houses. Consent should not prove too difficult. Why didn’t he ask? Why shouldn’t they affirm?

I fear the New York Legislature has lost its spine. This year, we Tompkins County voters will replace our retiring Assemblyperson. Seven Democrats have joined the hunt. But in none of three debates did any candidate raise the point of executive excess. A Party Committee member, I was tempted to proffer the question, but lost my nerve. But if I, myself, had run—though I may have lost—I would have made Cuomo’s power grab my campaign’s centerpiece.

To me, liberty matters more than anything else. Without the liberty and the license to legislate, the lawmaking branch walks only within the radius of the executive’s short leash. State Senators and Assemblypersons become subservient, not co-equal. Independent legislating evaporates. And if a representative may decide only those matters the governor delegates, those subjects too boring or politically worthless for his time and effort, the budding legislator might better stay home. It saves on gas.

On June 19th, Juneteenth, Andrew Cuomo delivered his final daily media address on COVID-19. No subordinates in sight. No reporters to question him. We found just Cuomo behind his desk; a briefing shorter than usual; under 1,400 words, a mere nine minutes. He reported lower hospitalizations, thanked essential workers, talked about “our better angels,” and of course, about himself:

“Love does conquer all. That no matter how dark the day, love brings the light. That is what I will take from the past 111 days. It inspires me and energizes me and excites me. If we could accomplish together what we did here, this impossible task, of beating back this deadly virus then there is nothing we can’t do. We will be better and we will be stronger for what we have gone through.”

Please, never speak that last sentence to someone who’s lost a parent, or a spouse, or a child to COVID-19. It bloats with insensitivity. But from Cuomo’s ‘til we meet again swan song, I will most remember its choreographed climax: A highly-produced, sweepingly-ethereal, mask-cluttered, Don’t-you-just-love-my-New-York-Tough-leadership tribute to the Empire State’s (purported) victory in the War on Germs—three-minutes of uplifting, Cuomo-narrated, self-congratulatory glitz, purchased, no doubt, with your taxes. Upon its crescendo, I imagined the stage lights to brighten, the candidate to beam, the convention delegates to applaud, as our Governor, at the podium, readied himself to accept the 2024 Democratic Presidential nomination.

Remember our Chief Executive’s parting words: “Don’t worry, I’m not going anywhere.”

Yes, King Cuomo, you—and we—deserve an intervention. A couple of years from now works for me.