Enfield may weigh-in on the Cargill controversy

Reporting and Analysis by Councilperson Robert Lynch; January 3, 2025

There are two sides to every important issue. Best we discuss them both.

The Town of Enfield’s borders don’t touch Cayuga Lake. Cargill Corporation’s sprawling underground caverns don’t snake as far as Enfield’s real estate. Nevertheless, the leader of Enfield’s Town Government, an environmental activist herself, believes her Town should register its opinion on whether New York State must take a more aggressive posture on mine reclamation plans; changes that environmental critics allege could permanently damage Cayuga’s lake waters.

Supervisor Stephanie Redmond almost succeeded in turning her Cargill-critical passion into an adopted resolution at the Enfield Town Board’s monthly meeting in mid-December. Her initiative stopped short of passage only because of another Board member’s unplanned absence and this writer-Councilperson’s assertion that Redmond holds an inherent conflict-of-interest.

Should Councilperson Jude Lemke return to the meeting table January 8th, the Cargill Resolution could be lifted from the table and voted on then. If so, most likely it would pass.

“We have an absolute duty to protect this lake, which currently is the drinking water source for 100,000 people,” Redmond asserted during an emotion-driven, risk-riddled seven minute monologue that went on and on, seemingly nonstop toward the close of the Town Board’s December 11th session. Quite obviously the Supervisor had recited each of the talking points from memory. Redmond had good reason to know them by heart.

Stephanie Redmond’s second part-time job is that of program manager for Cayuga Lake Environmental Action Now, better known by the acronym “CLEAN.” Of any group on the environmental Left, CLEAN stands foremost in attempting to block Cargill’s plans to continue mining salt beneath Cayuga Lake and doing so for the indefinite future.

And although the activist group may at times deny its true intentions for strategic reasons, CLEAN would prefer that not one more thimbleful of road salt be pulled from the depths of Cargill’s Lansing mine.

“We would like to take this opportunity to update you on the ongoing efforts of Cayuga Lake Environmental Action Now (CLEAN) to have Cayuga Salt Mine shut down,” CLEAN proudly proclaimed in the introductory paragraph of its most recent online newsletter to supporters, posted last May 17.

What the Enfield Town Board considered in December—and what it will likely resurrect January eighth—is a direct appeal to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). The proposed resolution’s density defies condensation. But cutting through the geologic gobbledygook, what the Resolution asks is for DEC to give the current Cargill permitting application much heightened scrutiny.

DEC administrators—presumably, scientists—have tentatively granted the Cargill application a “Negative Declaration” of environmental significance. The misleading, double-negative declaration would exempt Cargill from preparing a detailed and expensive Environmental Impact Statement to buttress its current plans. That declaration would also likely hasten the permit application toward approval. Moreover, the “Negative Declaration” would negate the need for public hearings, forums at which there’d be the predictable airing of Cargill-critical citizen comments.

“Various stakeholders, including environmental groups and local officials, have expressed concerns regarding the potential adverse impacts of Cargill’s proposed activities, highlighting the need for a more comprehensive environmental impact statement and public engagement,” a key paragraph in the resolution before Enfield lawmakers states.

It’s an “industrial waste site,” Supervisor Redmond pointedly described Cargill’s mine at one point in the December discussion.

It takes at least three affirmative votes to enact anything that comes before the Enfield Town Board, no matter how many members attend on a given meeting night. December 11th, Councilperson Jude Lemke had planned to attend remotely, but couldn’t. Councilpersons Cassandra Hinkle and Melissa Millspaugh—given their absence of objections—would likely have joined the Supervisor to provide the three votes needed for the resolution’s passage, that is until Redmond’s potential conflict-of-interest came to light. Parliamentary procedure considers an abstention the same as voting no.

“You will not have my vote on this tonight, this writer, Councilperson Robert Lynch, stated following Redmond’s reading of the Cargill Resolution.

“If the state regulators were saying that Cargill was in danger of polluting the lake or causing other environmental damage, you might have a different vote from me on this,” I acknowledged. “But what I fear is that regulations or resolutions like this are only going to serve one purpose, and I think that is the purpose that some people want to do, and that is to close the Cargill mine.”

Supervisor Redmond had given this Councilperson and others on the Board little time to do their homework. Although she’s a paid official of CLEAN, Redmond had sprung the agenda item to others in an email attachment at 8:30 AM on the day of the December evening’s meeting, a mere ten hours before the session would convene.

Drawing upon a trusted source in Tompkins County Government, this Councilperson brought to the table that night some statistics.

The Cayuga Salt Mine, I informed the Board, employs “more than 200 full-time employees in operations, maintenance, engineering, finance, management and support positions.” According to a recent independent study, the source had quoted me, Cargill contributes in economic benefits $4.6 Million to the Town of Lansing, $173 Million to Tompkins County, and $221 Million to New York State annually.

And if too many regulations burden Cargill, this Councilperson warned, and if too much pressure from New York State and its communities is brought to bear upon the company, “they’ll just fold up their hands and say ‘We’re leaving.’… There’s another business gone; there are 200 jobs lost.”

“And don’t think those 200 people are going to be retrained to be stockbrokers or computer programmers,” I added. “They’re going to be working at Walmart for a dollar over Minimum Wage. And I don’t want to see that.”

Stephanie Redmond views the economic tradeoffs differently. Like one or two prominent New York State lawmakers, Enfield’s Supervisor is willing to risk the loss of well-paying mining jobs to achieve a greater good.

“As far as the 200 people are concerned,” Redmond acknowledged as if to draw some economic equivalence, “we have over 60 thousand people locally that are part of our tourism.”

The Finger Lakes and the Great Lakes, the Supervisor maintained, supply 20 percent of the world’s fresh, accessible drinking water. Reprising a theme applied previously in a different context, Redmond predicted “climate refugees” will someday flock to Enfield and our region as they flee “smoke in California” or ocean-side cities swallowed up by rising tides.

“They’re going to come here (and say) ‘Oops, you salinized the water for the profit of a multi-Billion dollar company,’” Redmond forewarned. “It makes zero sense as to why we would sacrifice our grandchildren’s future for a Billion Dollar company so 200 people locally can have some money,” the Supervisor asked.

Supervisor Redmond’s up for reelection this year. Let’s see how much organized labor money she rakes in.

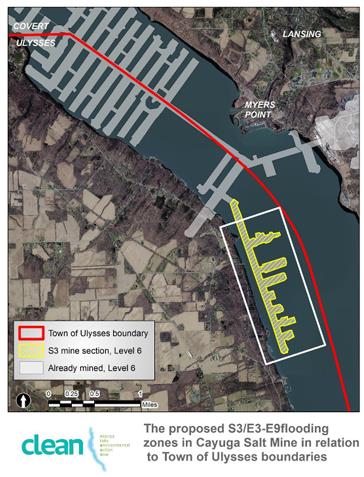

There was much more ground Redmond covered during her seven-minute Cargill critique. Central to the application currently before the DEC, Cargill proposes to flood the abandoned, so-called “S3 Zone” beneath Cayuga Lake with wastewater. The S3 Zone is down deep, maybe thousands of feet deep, but still close enough to the surface to bring Redmond worry.

Stephanie Redmond looked not just to tomorrow, but to a century or more beyond. The flooded salt pillars holding upper portions of the mine could erode, the Supervisor warned. Lakeside shorelines could collapse. “Salinization bubbles” could percolate upward into lake waters and kill brown trout. There could be a “catastrophic collapse” similar to that of the Retsof mine in Livingston County three decades ago. “They permanently destroyed the aquifer there,” the Supervisor asserted.

And she asked, what happens if Cargill does leave? The Supervisor predicted it’s a more than likely outcome, one to occur sooner rather than later.

“It’s a city under there,” Redmond reminded the Board of Cargill’s cavernous labyrinth beneath the lake. “There is no subsurface closure plan besides plugging the shaft,” she said. There’s no requirement that Cargill take out its underground trucks or pump out their hydraulic fluid.

And there’s a class warfare argument as well.

“Cargill is the largest privately-owned company in the United States,” Redmond asserted. “They have 14 Billionaires in their family alone.”

“They are benefiting, profiting off of our community resource,” Redmond alleged of Cargill’s Billionaire ownership. “We communally own the lake and the land underneath it.”

Our own Town Board was told that both the Lansing and Ulysses governing Boards had adopted resolutions encouraging DEC to demand a Cargill Environmental Impact Statement and seek public hearings. Each town borders Cayuga Lake.

The Ulysses Town Board acted November 12th, but sent a much-different letter to the state. That letter—and much of the Ulysses’ Board’s quarter-hour of discussion that night—dealt with whether the Town’s own zoning law holds any power over Cargill’s conduct. At least in theory Ulysses’ boundaries extend to the center of Cayuga Lake.

But New York State likely holds preemptive power in this instance. CLEAN’s lawyer had offered that some town authority might exist over mining conduct. But the Town’s attorney was said to disagree. The Ulysses Board voted 4:1 to send DEC the letter. While never stating his reasons with specificity, but perhaps guided by his board’s perceived overreach on the zoning question, Councilperson Michael Boggs cast the lone dissent.

After Supervisor Redmond had laid bare her extensive case against Cargill before the Enfield Town Board December 11, this Councilperson posed three questions to her:

Do you work for CLEAN, I asked? Yes, she does, the Supervisor answered. Do you draw a salary from them? Again, an affirmative response followed. And has CLEAN taken a position on this issue? Yes—of course— the organization has.

“Under New York State law, you have to abstain since you have a financial interest through your salary in the outcome of this Resolution,” I told the Supervisor. I recalled that when Redmond worked briefly as a state Assembly member’s aide, legislative ethics lawyers had counseled her never to take a local position on pending state legislation while holding dual responsibilities.

Redmond demurred. “This Resolution, whether it passed or not, would not affect my salary,” the Supervisor rebutted.

I respectfully disagreed with her assertion.

No lawyer sat in the meeting room that night. The matter went no further. Tabling until January served as the best of all options. And it preserved a slice of comity.

On the day of last month’s Board meeting, Supervisor Redmond had advised members of a December 20th comment deadline for any response they might make regarding Cargill’s permitting application. But now, CLEAN’s website lists a new, later, January 19th filing date. Enfield’s presumed comment, were it to be resolved at the January eighth meeting, would thus remain timely. Expect this two-sided argument to renew then… and perhaps extend for months beyond.

###