Reporting and Analysis by Robert Lynch; January 29, 2026

Labor goes first; management second in these sorts of things. And that’s the way it was Tuesday night as the Ithaca Board of Education granted final ratification to a new, three-year contract with its teachers union, a pact that on its surface appears to grant instructors and their bargaining unit just about every key provision they’d wanted. Teachers had ratified previously.

“As an educator, I am really excited about the vast majority of this contract,” Jacob Shiffrin, new to the school board this school year, said of the agreement. “That raise; that’s a kick-ass raise. It is far beyond what’s being given across New York State, and I think it’s really well-deserved.”

The triennial pact for teachers, a contract back-dated to last July, would grant instructors average seven percent salary increases this school year and again next year, followed by a six percent raise in 2027-28. But more importantly, the agreement puts in place a “step-and-lane” compensation plan that rewards teachers based on their experience and on academic credits gained toward professional development.

Ithaca teachers desperately wanted and fought hard for step-and-lane.

It’s almost unheard of for a school board to direct its negotiating team to bargain for minimally acceptable terms of an agreement and then reject the final work product. In my more than 50 years of watching local school systems, I’ve never seen that happen. Union rank-and-file, on the other hand, can prove fickle. So customary protocol calls for a tentative contract to go to union members first and be put to the elected board only thereafter.

Media reports tell us a full 86 percent of Ithaca Teachers Association (ITA) members approved the contract during a weeks-long ratification process that ended December 15. Teacher approval, and now the school board’s action, concludes negotiations that commenced last January. Negotiations aired publicly and proved at times tense.

Novel in the profession and not used locally before, the frequent, after-class bargaining sessions were open to the public and live-streamed on the internet. Despite the transparency—or possibly as a result of it—the union and the Ithaca City School District (ICSD) declared impasse last June. Everyone adjourned for the summer. Bargaining resumed in the fall, and both sides struck a tentative agreement in late-October.

When negotiators took sides last spring, teachers were asking for raises of about 7.5 percent. The district offered about 4.59 per cent, and without any step-and-lane sweetener. When accord was reached near Halloween, one could readily see who got the better of the bargain.

And from the words that flowed both from Board members and administrators prior to the January 27 ratification vote, one wonders whether management in those final negotiating days fought all that hard.

“Our contract puts our compensation model at the top tier of our region and our competitors; not in the middle, not in the median, but in the top tier,” School Superintendent Dr. Luvelle Brown crowed that night. “I now understand step-and-lane in ways I didn’t before, and I know that it’s mutually beneficial.”

“For me, this contract is legacy work,” Board President Dr. Sean Eversley Bradwell, a 17-year Board veteran, stated proudly. “It’s historic in a number of ways,” he said.

Eversley Bradwell, like Superintendent Brown, took particular note of the public face of negotiations.

“We were told time and time again, don’t do it,” the Board President recalled. Some skeptics, he said, “had reservations about disrupting a negotiation process that has been in place for decades.” But warnings aside, they still broke the mold. “That disruption from my perspective has proven to be fruitful,” Eversley Bradwell concluded.

The “fruits” of change, Eversley Bradwell recounted, included a video archive and a transcript. And from that transcript, he said, “you understand the nuance about the conversations.”

But there are two ways to view open-air public negotiations. They may have provided the process valuable transparency. But they also built a platform for teachers to advocate their positions in real-time for a willing audience to absorb. Instructors could co-opt those talking points to verbalize their grievances at the many ITA-organized protest marches that punctuated the protracted negotiations.

“Having things open has really given us a great chance to have a huge community conversation about our schools and our needs,” ITA President Kathryn Cernera told The Ithaca Times in an interview after the tentative agreement was announced.

The January 27 school board ratification was overwhelming, yet not unanimous. Jacob Shiffrin supported the agreement, yet dissented on grounds that in his view—one shared by at least two other board members—that more work needed to be done.

The ICSD-ITA contract runs 115 pages. And in Shiffrin’s opinion, some of its language—not related to step-and-lane, he qualified—raises “financial and legal concerns.” Those concerns, Shiffrin maintained, could be “tweaked within a few sentences,” and could be resolved in “one brief bargaining session.”

Colleagues Emily Workman and Todd Fox voiced similar concerns, yet each voted to ratify the contract.

“I thought about voting against it for the sake of hopefully trying to clean up some stuff that down the line could cause serious issues for the district,” Fox announced.

“I’m excited to vote in favor of this resolution, and yet I’m doing so with some reservations,” Emily Workman said of the contract. “On the balance, I’m voting yes because I believe the pay increase for our teachers is rightly important and very, very well-deserved.”

Neither Workman’s “reservations” nor Todd Fox’s “stuff” got detailed during the meeting. But Eversley Bradwell did comment that to him, “All the concerns that have been expressed to me are ‘wins’ for teachers.”

Noticeably absent from the school board’s discussions was any serious consideration of the contract’s impact on future operating budgets or the Ithaca City School District taxpayer. Indeed, the evening’s focus on personnel and program benefits produced a lopsided discussion for any objective observer.

Even though the annual ICSD budget vote stands less than four months away, Board planning for the 2026-27 ICSD budget remains in its infancy, at least from the public’s perspective.

The closest we’ve gotten so far came at an open-ended, 45-minute roundtable discussion during the school board’s prior meeting, January 13. Superintendent Brown and his financial assistant provided only preliminary forecasts. A PowerPoint slide roughed-in a stated $174.5 Million in budget revenues and a property tax levy of $107.2 Million. But the numbers were never fully explained. A $174.5 Million budget, if that’s the case, would mark a modest 3.25 percent rise above the $169 Million dollar budget for the current year.

Expect ICSD budget planning to begin in earnest come February.

“We have been assured by Dr. Brown and his team that we can afford the costs associated with a number of the provisions in the contract,” Emily Workman stated in defense of her ratification vote. And, “from the financial information that has been provided to the Board, it looks like we can,” she said. Workman’s comment was about the closest any Board member came January 27 to discussing the agreement’s fiscal implications.

That said, Workman voiced unspecified questions “about the potential impacts of the reallocation of moneys and use of the district’s reserves.” Those “reservations” made Workman’s support but lukewarm.

Elections matter. And one wonders whether a labor contract like the one ratified Tuesday night would ever have been reached had Jill Tripp still been on the Ithaca Board of Education.

Noted for her frugality, her influence, and her outspokenness, Jill Tripp was voted off the Ithaca school board last May. In contrast with the taxpayer revolt of the 2024 election, Ithaca City School District voting last year marked the electorate’s generally-predictable return to its left-of-center preferences. Program preservation overrode austerity. Each of the four candidates who secured school board seats in 2025 carried the ITA’s endorsement. Jill Tripp had not earned it.

School boards set negotiating strategies during closed-door executive sessions. And it’s there where administrative bargainers get their marching orders. Had Jill Tripp huddled in those meetings last fall, she might have urged a tougher bargaining line.

Inexplicably, between the declaration of impasse in June and the reaching of a teacher-friendly agreement in late-October, the gap between labor and management narrowed. Yes, there were marches and rallies last fall. But for reasons unstated, teachers found getting what they wanted a whole lot easier.

During the talks, Ithaca teachers had complained that formerly-existing compensation policies—and particularly the absence of step-and-lane, had placed them and the ICSD at a disadvantage. Good teachers went or stayed elsewhere. But that was then. Superintendent Brown now believes the tide has shifted.

“I can now say that the product (of these negotiations) is one that puts us as one of the most competitive and most attractive school districts,” Brown said during Tuesday’s meeting. “This is one of the best school districts not only in our state, but in our nation, and I think this contract represents it,” the Superintendent heralded, “and it’s a mutually-beneficial one, and I will say that to anyone, and we can afford it.”

Affordability, of course, is a discretionary standard. One person’s economy is another’s reckless spending.

Recognize “the realization of how deeply flawed the funding of public schools are—it’s absolutely broken,” Erin Croyle, one of Board of Education’s more progressive voices, imparted during the January 13 first-round budget talk. “I know that our tax bills in this town are just absolutely unsustainable and ridiculous,” she acknowledged. “But I also know that it’s not like we’re—we truly are not spending in an inappropriate manner here in our district.”

Erin Croyle moved to adopt and then voted for the three-year ITA contract two weeks later, yet said little else that night about it.

“I feel proud about legacy work,” Sean Eversley Bradwell said just before calling the ratification vote. “I feel proud about a contract that is historic and will mark time and educational spaces.”

Teachers like this contract. The Ithaca Board of Education likes this contract. We may find out what voters think of it come May 19.

###

TCCOG Wanders in the Wilderness

Intermunicipal group seeks new home, new voice, new rules

Analysis and Commentary by Councilperson Robert Lynch; January 25, 2026

“My opinion is that the Tompkins County Council of Governments is a public meeting body. It meets all of the requirements.”

Tompkins County Attorney Maury Josephson; December 11.

“We’re just a voluntary group of people getting together to decide mutual issues; we’re not a governmental body.”

Jude Lemke, Enfield’s new TCCOG representative, January 22.

****

For the past six years, ever since 2000, this Councilperson has represented our Town of Enfield on the Tompkins County Council of Governments, better known as TCCOG. I no longer do. This January, the Town Board’s majority voted a change. I was replaced. I did not object. And I’m glad that I did not. If ever there was a moment for the past to exit and the new to arrive, that time is now. With the start of this New Year, perhaps more than at any other time in its 20-years of life, TCCOG has moved to reinvent itself. At least it’s trying to.

Some around Enfield and County Government may accuse me of writing a hit piece. This is not that. There are too many good people on TCCOG. I hope to continue working with them in other capacities. What I write here is part reporting and part constructive criticism; a former member’s pointed evaluation of an organization that in recent months met a fork in the road and then in my opinion chose the wrong path.

The last meeting I’d attended as Enfield’s representative was last December 11. On that day, we set our 2026 meeting schedule. As usual, we’d planned to convene roughly once every other month. We set our first session for 3 PM on Thursday, January 22. We’d meet in Tompkins County Legislative Chambers, as we always have. There’s always an online option for those who’d rather stay close to home.

But then during the days before January 22, I noticed something amiss. The six upcoming 2026 meetings were no longer posted on the Legislature’s meeting portal. The upcoming YouTube tile for public attendance and after-meeting viewing had disappeared. And unless—like me— you’d emailed multiple County officials and at least one continuing TCCOG municipal member beforehand, you’d never have known the group had actually planned to meet. In fact, you might have suspected TCCOG had disbanded.

But TCCOG had not dissolved. And TCCOG, indeed, did meet. And it met at its appointed day and hour, just not at its designated place. TCCOG held its January session only on a Zoom portal. And yes, I was its only non-member who found his way into the meeting.

What’s more, don’t expect to ever see or hear anything that was said or done that day. Meeting leaders admitted they hadn’t recorded it.

Welcome to the TCCOG of 2026; the organization as it prepares to enter its third decade. You may ask why does anything I’ve written here really matter. Or to grind a sharper point, why does TCCOG itself matter?

Well, it matters because over two decades, the Tompkins County Council of Governments has done a lot of good things for Tompkins County and for its people. TCCOG’s municipal members, convened together, have planted the seeds for strong initiatives that later grew to become law or policy or institutional structure. And by and large, TCCOG has made those decisions and recommendations out in the open for all of us to view.

In its earliest days, TCCOG drove the initiative that led to creation of the Greater Tompkins County Municipal Health Insurance Consortium (GTCMHIC), the Ithaca-based alliance that pools local governments to buy employee health insurance at cheaper rates. Consortium participation now reaches across the Finger Lakes.

TCCOG has worked toward extending broadband Internet to every nook and cranny of Tompkins County. And most recently, the organization has played a vital role in modernizing local emergency medical response services.

Created by the Tompkins County Legislature, TCCOG invites each of our county’s nine towns, six villages, and the City of Ithaca to designate one member and one alternate member. TCCOG meets bi-monthly. (It once met monthly). It passes resolutions by majority vote, each member’s vote carrying equal weight regardless of a municipality’s size or influence. And TCCOG then passes its recommendations on to the County Legislature, and sometimes to New York State lawmakers.

That’s what TCCOG is and where it’s been. Now the question is, where’s it heading?

One place where it’s obviously not heading is back to Tompkins County Legislative Chambers.

“Korsah, Deborah and others had to meet to decide how to hold this meeting,” TCCOG Co-Chair Dan Lamb conceded at one telling moment January 22. Lamb referred to County Administrator Korsah Akumfi and Legislator and newly-appointed TCCOG rep. Deborah Dawson as he revealed that theirs had been very much a hurried mission driven under duress.

During the final months of last year, a rift had opened between certain members of TCCOG leadership and the County Legislature’s Clerk over whether and to what extent TCCOG fell under the dictates of the New York State Open Meetings Law (OML). Tompkins County Attorney Maury Josephson had sided with the clerk, Katrina McCloy.

Both Josephson and McCloy had insisted that TCCOG should comply with the OML. But at the earlier, December meeting, a straw poll had been taken and showed member sentiment otherwise. The online video screen showed no more than two attending members believed TCCOG was legally required to follow the OML. Only Cayuga Heights Mayor Linda Woodard and this writer were shown raising our hands in support. County legislator Dan Klein may have concurred, yet off-screen.

At the January meeting, little was said as to why meetings were no longer in chambers apart from Lamb’s quoted moment of candor. Was TCCOG evicted? Did leadership leave voluntarily; or maybe in disgust? Those closest to the decision don’t want to discuss it, other than to make firm that from here forward, Tompkins County Administration, not the Legislature’s office, will provide TCCOG its staff support.

“We are happy to administer the meetings,” County Administrator Akumfi advised the session.

That said, quite clearly this new assignment had been dropped into Administration’s lap with minimal forethought or preparation. December meeting minutes weren’t ready for January approval. A public meeting link never went up that day. No recording was made. And no one could tell membership how those things would be dealt with for the next meeting in March.

How will the Zoom link be established for members and the public, someone asked. “We will work through it administratively,” Akumfi answered. “We have two months to work through it,” he said.

“How’s the public going to find out?” Danby Supervisor Joel Gagnon followed up.

“We’ll know more (about how to do it) when Korsah figures it out,” Lamb told his Danby colleague.

To some, those responses may less than reassure. The public never knew of the January 22 meeting. Who says they’ll know about the one that’s planned for March?

“We’re all concerned about transparency, and now we’ve made ourselves less transparent,” Ulysses Supervisor and TCCOG Co-Chair Katelin Olson rightly observed.

At its December meeting, a session that feels like so long ago, Dan Klein, then Chair of the Tompkins County legislature, but now retired, presented a multi-point resolution for TCCOG to consider and adopt. The resolution would have affirmed TCCOG’s compliance to the Open Meetings Law, even for its sometimes-secretive “subcommittees” (now rebranded as “working groups” at the January session.).

After debating Klein’s resolution to the point of deadlock that December day, and with meeting chambers soon to darken and clerks to go home, this Enfield Councilperson moved to table the Klein motion for one month and pick it back up in January. That was the last time the Legislature Chair’s motion ever saw the light of day.

With both Klein and his motion now gone (and with me as a member gone as well), TCCOG leadership, under Akumfi’s guidance, brought something totally new to the Zoom room in January. Under whose parliamentary rules that was done, one can only guess.

What emerged instead for members to consider was a wordy, two-page, resolution “Establishing the Structure and Consistency for Accurate Record Keeping of (TCCOG) Meetings.” It started out with 18 “Whereas” qualifiers followed by ten bullet-pointed commands. Eighteen and ten, that is, before membership started cutting.

The closest the new text came to what Dan Klein had wanted was to pay brief deference to the acknowledgement that “the Tompkins County Attorney believes TCCOG to be subject to Open Meetings Law.” But TCCOG members, by amendment, cut that sentence out.

Instead, the January adopted resolution, stressed that:

- TCCOG is not an agency or sub-agency of Tompkins County;

- TCCOG is not a government, does not have jurisdiction nor authority to enact or enforce regulation of any kind; and

- TCCOG decisions are non-binding on its membership.

That said, the resolution—which by a show of hands appeared to hold unanimous support—still called for all meetings to be noticed, to be open to the public, and to have minutes produced and a recording made publicly available, but only “if a recording of a meeting is produced,” the resolution qualified.

Notably, a final bullet point clarified that the afore-mentioned requirements “do not apply to work groups of TCCOG.” Those sub-groups can be as private as their members prefer, it seems.

“We’re just a voluntary group of people getting together to decide mutual issues; we’re not a governmental body,” Councilperson Jude Lemke, Enfield’s newly-named TCCOG representative, stated.

Nobody much disagreed with Lemke’s assessment that day.

But square the Councilperson’s opinion with that of Tompkins County Attorney Maury Josephson, who in December advised TCCOG the following:

“My opinion is that the Tompkins County Council of Governments is a public meeting body. It meets all of the requirements,” Josephson insisted. “It requires a quorum to meet. It conducts public business… and it performs a governmental function.”

The County Attorney cited that day’s own discussions of countywide emergency medical response and TCCOG’s possible EMS funding recommendations to the County Legislature as evidence to underscore his position.

“TCCOG is able to effectively recommend legislation to the County Legislature,” Josephson pointed out. “The issue that has been raised is, is this body purely advisory, and it is not,” he insisted. “If the committee (that is, TCCOG or its sub-group) is voting on what the law is, as County Attorney, I can’t recommend that the County pursue initiatives that are in violation of applicable laws.”

Jude Lemke and Maury Josephson are each lawyers. Attorneys get paid to argue, of course. But from the January 22 discussions what’s become ever so apparent is that with the transfer of TCCOG’s oversight from the Legislature to the County Administrator, Maury Josephson’s opinion doesn’t seem to count for much anymore.

Right now, the Tompkins County Council of Governments has no real home; that is, no physical meeting place aside from cyberspace. It may never have one again.

“It’s nice to have an in-person option,” Dan Lamb acknowledged, even though he conceded remote attendance is easier. Expect Zoom to become the only option of choice from here on out.

“The Zoom meeting is just fantastic,” Caroline’s Mark Witmer chimed in. Still, had TCCOG remained controlled by the Open Meetings Law, its having a physical location with a quorum present there would likely have become a pesky requirement.

Legislative clerks had complained that counting votes at TCCOG has become a problem for some time. Members raise hands, especially online. Clerks found it hard to preserve for the minutes whose side had the majority. Clerk McCloy had requested a roll call requirement. The new, January resolution had initially carried forth McCloy’s roll call rule, only to have an amendment strip it out.

“You don’t have to make the clerk happy anymore,” Legislator Dawson remarked. Perhaps she spoke in jest. One couldn’t tell.

As I said, it’s a new TCCOG. And it’s one where I no longer vote. Given what’s happened, I’m kinda’ glad I no longer do. Maybe fate did me a favor..

###

And here, what you should expect from this website going forward:

… and then there was change

by Enfield Councilperson Robert Lynch; January 15, 2026

I launched this website, bob-lynch-enfield.com, in April 2019. The website was born during my initial campaign for Enfield Councilperson. Back then, what I wrote was mostly introductory stuff. I provided information to inform you of who I was and why you should vote for me. It was a campaign website limited in its purpose. That’s what you’d expect.

And at first I didn’t write much about the events happening around us. Over time, the emphasis changed. This website evolved. Campaign victories left a void to fill. I filled it with news.

Among the initial essays I’ve raised from the dust is one I’d posted in September of that first year. I’d responded to a lengthy political commentary written back then by a former Enfield Town Supervisor who never liked me very much; a person best forgotten, someone no longer a community resident and whose words and actions I forgave long ago.

I revisit that essay because I quoted in its heading the words of a woman and political leader I respected then and respect even more today, former Vice President Kamala Harris:

“I was raised by a mother who said many things that were life lessons for me, including, ‘Don’t you ever let anybody tell you who you are. You tell them who you are.’”

The essay I wrote had attempted to carry forth Vice President Harris’ admonition as I addressed the troubling, untruthful insinuations that had been hurled at me. I wrote, “When anger overwhelms civility and reasoned judgment, facts get distorted, quotations twisted, and political ignorance rewrites the truth.”

One of my earliest news stories posted here came in January 2020. It reported the Tompkins County Democratic Committee’s endorsement of Tracy Mitrano to face Congressman Tom Reed in that November’s General Election. (Mitrano, of course, lost.) I happened to be a member of the Democratic Committee at the time. I’d voted on the endorsement. Was there a conflict of interest in my writing that story? You decide.

Over the years, I have employed this website to report on actions and controversies involving the Tompkins County Legislature, the Ithaca Board of Education, and here, most to the point, the Enfield Town Board, the governing body on which I sit.

Some have thanked me for the work I’ve done, for the information I’ve conveyed. Others have not. Many of my toughest critics hold positions of power and influence, either present or former, in local government. These people would rather I shut my mouth, exit my keyboard, and keep my thoughts to myself. They’d have me refrain from any attempt to report what I see and hear. They allege that any reporting I do compromises and conflicts with my governing responsibilities as a municipal leader.

James Madison and Alexander Hamilton helped frame the U.S. Constitution. They played key roles in the constitutional republic that they had helped build. But they also wrote much of The Federalist Papers, a series of advocacy essays that influence our constitutional understanding to this day. I would never place myself on an equal plane with the founders of our nation. But I never recall anyone challenging Madison’s or Hamilton’s written advocacy as a conflict with either man’s former or future governance. If any had thought of doing so, they dared not state it.

But maybe newswriting is different? Journalism was my first career. And the instincts engrained within an inquisitive reporter will forever rest within his being. More than any other attribute, my desire is to search for facts kept secret; uncover them, analyze them, and then share them with others. It defines the person I am. This talent, sharpened through experience, will never leave me. Understand that.

I have a style of newswriting some do not like. They find me too critical. I beg to disagree with those detractors. I take pride in how I practice my craft. I peer behind the curtain. I ask questions that maybe no one else will ask. I stand guard against fabrication, equivocation, or flawed reasoning, whether the words come from the President of the United Sates or from a town highway superintendent.

Some have labeled my writing “tabloid journalism.” I call it reporting and writing with candor, honesty and an edge. I do not refrain from calling events as I see them; from drawing conclusions as objective insight pulls me into them. I recognize nuance and respect context. I attempt to put matters into reasoned perspective. I attempt to tell you not just what happened, but also why it happened and why what happened should matter to you. That’s why the stories you read here may delve deeper into a controversial topic than those others write. And you may read stories here that you will find nowhere else.

Case in Point: On January 6 of this year, I wrote how the Enfield Board of Fire Commissioners had—in the words I chose—“ditched” The Ithaca Journal as its designated newspaper for publishing legal notices in favor of Tompkins Weekly. To offer perspective, I reported that in so doing, the Board of Fire Commissioners was “going to a place where Tompkins County (had) chickened out.”

I’ve been criticized for the comparison that I drew. One community leader did not welcome the candid assessment. It was bluntness with a sting, to be sure. It was also true. I stand by it.

As I’d reported in a story posted November 21, the Tompkins County Legislature November 18, in stand-your-ground defiance, put itself at odds with its County Attorney, its legislative clerk, and likely New York State law. Legislators defeated, two votes to 12, an otherwise-routine annual designation of The Ithaca Journal as the official newspaper, thereby denying the Gannett daily its monopolistic ability to extract tax dollars in exchange for publishing legal ads. Annual designation makes the Secretary of State happy, and counsel claimed that only the Journal qualified.

Defiant legislators that November night wanted state law updated, drawn into the 21st Century, to the era where online publications get more eyeballs than does a cranky old Fishwrap like The Journal. They’d punish a paper that charges exorbitant ad rates, gets delivered only by mail carrier, and no longer covers local news in the first instance.

I quoted one legislator this way:

“I think we all understand our right to protest,” Dryden’s Greg Mezey, leader of Tuesday’s anti-Journal rebellion, made clear. “I think sometimes as a lower level of government, we need to rise up and use our voice and our platform to encourage the state to move more swiftly.”

I granted the Legislature’s thumb-in-the-eye revolt against same-old, same-old more than 1,200 words. Tompkins County’s official post-meeting press release accorded the action 76 words. The Ithaca Times gave it 158. My story assigned the defiance top placement, as my news judgment dictated. The others buried the decision beneath the meeting’s more predictable actions.

Fast-forward two weeks, and to the Legislature’s next meeting, December 2. Greg Mezey, who’d voiced rebellion a fortnight earlier, conceded defeat:

“It’s like falling on a sword,” Mezey said, “as much as it pains me to move [to reconsider.] “Friends, we had our opportunity to stand up to higher levels of government and protest… But here we are. This needs to pass.”

And pass it did, ten votes to four. Only Mike Sigler, Anne Koreman, Travis Brooks and Deborah Dawson held true to their principles. Dawson peppered her dissent with these words: “We really need to point out to Albany that The Ithaca Journal sucks.”

I heard the words, I recorded the votes, I read the room, I drew my inferences, I wrote what I had found and as I had found it. And when later the Board of Fire Commissioners took a divergent path, I drew a comparison. I stated it bluntly. I think I did good work. And well, I rest my case. (And lest you think otherwise, legislator Mezey was not the leader who faulted me for my reporting.)

With the turn of the calendar, the sands have shifted down at the ornate Gov. Daniel D. Tompkins Building, Legislative Chambers. With the start of 2026, fully one-half of the newly-expanded, 16-person County Legislature is brand new. Some venerated traditionalists have left. A few Young Turks have taken their place. And one of them is very young; he’s just out of college. I know when it’s time to say goodbye. As I‘ve appended to my final legislative story, dated January 9, I will no longer report on meetings of the Tompkins County Legislature. Let others do it.

Now to Enfield. Here lies a problem somewhat different.

Trust me, at every meeting of our Enfield Town Board, I wish there was some brave soul out in the visitors’ gallery with a pencil in her hand, a notebook (or a computer) on her lap, and an employer who commanded she be there. Sadly, there is no such person. But if there was, I would not need—nor choose—to report what occurred that night. I’d prefer someone totally impartial and detached from Enfield Government chronicle what we do every second Wednesday of the month. And let that person be as brutal as he or she wants to be regarding what I say and do. I’d welcome it. I can defend myself.

Yet for the mainstream Ithaca media, the reality is this: The Town of Enfield is the smallest town in Tompkins County and lies at the bottom of the informational food chain. It always has been. When I cut my teeth as a radio reporter in the 1970’s, it was like that too. Cover the Enfield Town Board only when nothing else is happening or when something big in Enfield blows up. (And back then, Ithaca Common Council met the same night.) Ordinarily, the best we could do is phone then-Supervisor Robert Linton the next morning and have him summarize what happened; that is, only if we thought of it.

I may never convince some of those I sit with that I do not write what I write purely to criticize or diminish them, to place their words, their actions, and their personalities in the worst possible light. That is not why I write about what we do. I write because all too often in Enfield government trees fall in the political forest and no one hears them crash. For those who do not know about or read this website, the refrain heard too often carries surprise. “When did you do that?” they say. “I didn’t know you were considering that.” The remark usually follows—often by months—some Town action that curtails freedom or raises taxes.

Much discipline goes into everything I write and post on any Enfield story. I cannot rely merely upon my mental recollection or on scattered, scribbled notes taken by me at a board table when I’m transacting business. Bias or selective memory may creep in were I to do so. That’s why it may be days, even weeks, before an action of the Town Board gets reported. I must revisit the meeting’s audio recording, listen and transcribe what was said, words spoken not just by others, but also by me. Did I get the facts right, the votes right, the quotes right, and did I place them in proper context? Trust me; it takes hours, sometimes days, to complete that task. It’s hard work. And I do it because nobody else will.

For months, indeed years, I’ve agonized over the conflict that lies at the heart of the decision I must make: How do I fulfill a self-set duty to provide Enfield’s residents, our constituents, timely, accurate information and at the same time honor my foremost responsibility to provide those in Enfield effective, impartial leadership without compromise. With the decision I have reached today, I conclude that I cannot do both.

I intend to serve out my four-year term as your elected Councilperson, a term running through December 2027. At this point, I also plan to seek re-election, barring the arrival of some unforeseen circumstance. So for at least two more years, and maybe longer, the conflict that I face is the conflict that I must resolve.

I will resolve it this way: For the remainder of my tenure on the Enfield Town Board, I will not report on Enfield political decisions and deliberations in the way I have done so for much of these past six years.

I will inform, but in a different way. As time permits, I will post Town Board actions or decisions on this website, doing so in a cold, factual manner, with each issue’s prioritization tempered by my news judgment. You’ll find little context; minimal controversy; and news that’s bland and oftentimes boring. Sorry, but expect it. It may not entertain. It may not sufficiently inform. But it may placate my critics. And it will make my own life a whole lot easier.

I make one exception to this general rule. Since my political committee owns this website and I control its content, I reserve the right to quote my own statements made at Town Board meetings as an exercise of my First Amendment freedoms. I may also write commentaries from time to time on issues I deem of importance to Enfield and Tompkins County.

Those who serve in local government; in Tompkins County Legislative Chambers, but also in Ithaca City Hall, should be damned glad that they serve now and not 50 years ago. Back then, The Ithaca Journal had perhaps a half-dozen news hungry reporters on its City Desk. And competing radio stations fought to be first with every story. No one, not in politics, business, or community leadership in general, stood immune from examination. None could get away with half of what they find possible to get away with today. An inquiring press does that, and democracy benefits.

I remember how it was. I wish it was still that way. But it is not. I’ve attempted in some slight way to fill the vacuum. But because of what I have written here, I can no longer step forward on my own and light that one little candle to help illuminate the darkness.

Good luck. I hope that before I leave elective office I spot that single lowly reporter sitting in the gallery of our Enfield Town Board, pencil in hand, notebook on lap. But that person cannot be me. I have standards to uphold, my character to defend. I have another job to do. And only I have the right to define who I am.

Peace,

Bob Lynch

###

And now, to the news:

Amid packed house, Tompkins sends message on Data Center

Highlights of January 20 meeting; Tompkins County Legislature

Reporting courtesy: Tompkins County Department of Communications; Monika Salvage, Communications Director; January 23, 2026

Legislator Dawson (D-Lansing, Ithaca Town) presented a Resolution Requesting New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to Reject the Modified Water Withdrawal Permit Application from Cayuga Operating Company, LLC and Instead Require a New Application and Environmental Review Process. A large number of individuals in support of the resolution filled the legislative chambers that evening.

Speakers expressed concern that the proposed AI data center in the Town of Lansing represents a significant change from the former coal-fired power plant and should not be allowed to proceed under an existing or modified water withdrawal permit.

Speakers cited risks to Cayuga Lake from the proposed project, including potential thermal pollution, harmful algal blooms, chemical contamination, harm to aquatic ecosystems, and long-term impacts on wildlife and drinking water. Many questioned the accuracy and transparency of the applicant’s claims regarding closed-loop cooling and water use, noting conflicting statements and permit filings that suggest large-scale withdrawals could occur.

Additional concerns included increased electricity demand leading to higher energy costs for residents, noise pollution, climate impacts, and inadequate oversight or accountability by state regulators. Overall, commenters urged a full environmental review, a new water withdrawal permit, and stronger protections to ensure public resources are not compromised and costs are not shifted onto the community.

Most legislators spoke in support of the resolution, emphasizing accountability, transparency, and the need for a new water withdrawal permit and modern environmental review given the site’s proposed shift from a retired coal plant to a high-intensity data center. Supporters stressed that the county lacks land-use authority but has a responsibility to urge the DEC to apply current environmental standards, particularly to protect Cayuga Lake.

Legislator Weiser (D-Caroline, Danby) urged colleagues to hold DEC accountable.

“Given the age of the permit, the absence of modern monitoring requirements, the lack of reliable historical withdrawal data, and the material change in use, there is no regulatory or environmental justification for treating this as a mere modification, ”Weiser stated.

Legislator Sigler (R-Lansing) cautioned, “I think you’re rolling the dice on this. I think this resolution might open the door for DEC to open up the existing license to other uses.”

The legislature approved the resolution with 14 votes in favor, 1 opposed (Legislator Sigler, R-Lansing), and 1 recusal (Legislator Wakeman, D-Dryden).

[Note: Between community activists and legislators, discussion of the Dawson Resolution regarding the Lansing data center occupied a full two hours, more than half of the meeting.]

****

Chair’s 2026 “State of the County” Address:

Chair Shawna Black delivered the State of the County address, highlighting the county’s current status, its accomplishments in 2025, and how shared priorities are shaping the year ahead. Selected excerpts follow:

“Tonight, I’m honored to share the State of Tompkins County. I am confident in saying: The state of this County is strong, resilient, and determined.

“Strong because the strength of this County comes not from one single person, but from our collective commitment, especially the commitment of this Legislature and the dedicated County staff who turn policy into real-world impact – every single day.

“Resilient because even with rising costs, housing pressures, federal uncertainties, and growing service demands, Tompkins County continues to deliver. The story of this past year is one of dedicated public servants, strong partnerships, and a clear commitment to serve all of our community members.

“Determined because we stand by our values of respect, accountability, integrity, equity, and stewardship. A few weeks ago, we welcomed eight new legislators to this body alongside eight returning members. That infusion of fresh perspectives, energy, and lived experience has already deepened our deliberations, sharpened our questions, and strengthened our ability to make difficult decisions with integrity and care.”

[Chairperson Black also announced her 2026 legislative committee assignments. For those legislators who represent Enfield, Randy Brown will newly-chair the Government Operations Committee and sit on both the Budget, Capital and Personnel Committee and the Facilities and Infrastructure Committee. Newly-elected legislator Rachel Ostlund will become Vice-Chair of the Public Safety Committee and sit on the Health and Human Services Committee and on a newly-formed committee charged with review of the County Charter.] [No members were named to what had been the Downtown Facilities Special Committee, a committee that Randy Brown had chaired, leading to the inference that Shawna Black may disband that committee. / RL]Other Legislative Business:

- Following a search process and a recommendation by the county administrator, the legislature unanimously appointed Charles Githler as the new County Historian. Mr. Githler taught American History for 17 years at Newfield Middle and High School. He served as a board member of the Newfield Historical Society and is a current trustee of The History Center in Tompkins County. He succeeds Carol Kammen, who served in this role for over two decades and retired at the end of 2025.

- The county administrator and deputies presented highlights of the critical work county departments accomplished in 2025. Organizational achievements included filling key positions, such as Commissioners of Whole Health, Department of Social Services, as well as Finance and Highway Directors. The county secured grant funding that reduced the local cost burden, including for the Assigned Counsel program, assessment system modernization, supporting young parents at DSS, expanded GIVE funding for public safety and probation initiatives, federal funding for the airport, and for food-waste reduction. The Planning Department awarded grants for affordable housing projects through the Community Housing Development Fund.

###

Updated: Costly Culvert Bids Boggle Enfield Board

by Councilperson Robert Lynch; January 16, 2026; updated January 20, 2026

(Update; Jan. 20): In a 3-1 decision, providing the bare minimum number of votes to pass, the Enfield Town Board Tuesday accepted the lowest of three bids and remained with its original plans to purchase a concrete box culvert to place under Bostwick Road later this year.

By accepting Jefferson Concrete Corporation’s offer of $471,600, the Town Board’s majority cast aside a likely less expensive option that would have built the culvert out of aluminum sections, rather than concrete.

Options presented at a January 16 planning meeting, which two Board members attended, projected the aluminum culvert’s price—and the project’s total cost—at about $200,000 less than that of the pre-cast concrete design.

The Jefferson Concrete bid, among the three opened earlier this month, came in approximately $200,000 above what project planners had initially forecast.

Enfield Town Supervisor Stephanie Redmond persuaded the Town Board’s majority Tuesday that changing course now and switching to aluminum, held too much uncertainty. That uncertainty included the prospect that the New York State Department of Transportation might reject the aluminum alternative, force the Town to stay with concrete, and delay the project until next year, when construction costs could grow considerably higher.

Councilperson Robert Lynch, the lone dissenter, maintained that going with the cheaper option was worth the risk, given the potential savings.

Recalling Enfield’s 2023 controversy over purchasing an $830,000 fire truck, Lynch predicted that were the culvert project to be put to a public referendum, voters would reject it.

Enfield Councilpersons Cassandra Hinkle and Melissa Millspaugh joined Supervisor Redmond in supporting the concrete culvert’s purchase. Councilperson Jude Lemke was excused from the meeting.

****

The original story follows:

This isn’t the way the Enfield Town Board had hoped to start the New Year.

Bids for a giant concrete culvert to be placed under Bostwick Road not far from Route 327 came in way over estimate when those bids were opened earlier this week at the Town Clerk’s Office.

“We are going to be way over,” Town Supervisor Stephanie Redmond remarked as Clerk Mary Cornell January 12 unsealed the three submitted offers, one by one.

Of the three, a Watertown firm, Jefferson Concrete Corporation, submitted the apparent low offer of $471,600. The cost covers the concrete culvert’s manufacture and delivery alone, not its installation.

Officials had earlier estimated that the culvert would cost around $200,000. But heftier design specifications demanded by New York State had heightened the price, as had inflation.

The Town Board had planned to review the bids and then award one of them at its Regular Monthly Meeting Wednesday, January 14. The board somewhat accomplished the first task, but never got to the second. After briefly inspecting the offers that night, the board postponed action to seek more information.

The Town Board will likely decide its course of action at a Special Meeting Tuesday, January 20. The meeting had been called for other purposes, but Supervisor Redmond has added a culvert decision to the agenda.

When it next meets on the 20th, the Town Board could either award Jefferson Concrete’s low bid, rebid the purchase (although unlikely), or reject all bids in favor of a potentially less costly option.

From roadside, the Bostwick Road culvert project looks like a routine repair. But when two Town Board members, Enfield’s Highway Superintendent, and project officials convened Friday, January 16 to discuss alternatives, project Engineer Brian Reaser outlined the scope differently.

It’s going to look like they “threw a whole bunch of grenades and blew the whole thing up,” Reaser told attendees of what the site may look like this summer. There’ll be a “massive adjustment of what the scenery looks like,” he warned.

Should Enfield officials proceed and award the lowest submitted bid, culvert replacement would likely occur late this summer. Bid papers call for the supplier to deliver the box culvert no later than September first.

Submitted along with Jefferson Concrete’s $471,600 bid January 12 were those of Lakelands Concrete Products of Lima, NY for $684,514, and Binghamton Precast & Supply Corporation’s bid of $705,800.

In 2024, the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) awarded Enfield a Water Quality Improvement Project (WQIP) grant of $693,866 for the Bostwick Road culvert replacement and stream relocation. Actual receipt of the grant award was delayed for months by DEC foot-dragging. The delay prevented the culvert’s replacement during 2024. Post-award engineering studies further precluded construction during 2025.

Supervisor Redmond advertised the request for project bids last month. For the sake of expediency, the Supervisor bypassed holding a formal Town Board authorization vote so close to Christmas. Redmond has stressed that offers needed to be awarded by January to assure timely construction.

But disappointment overcame all present the afternoon that Clerk Cornell opened the bids. And part of the problem, Town officials were told, rests—perhaps predictably—with New York State.

“Regulations have changed and been updated,” Angel Hinickle, Resource Conservation Specialist for the Tompkins County Soil and Water Conservation District, informed those present that day. The state now mandates a ten percent increase in culvert size to address predicted climate change, she said. At the January 16 conference, Hinickle also said that New York requires any culvert’s top to stand at least one foot above water level during a; “100-year flood.”

Enfield Creek, whose water would pass through the culvert, lies within the recently-designated Enfield flood zone.

There’s a second complication created by New York State. In late-December, Governor Kathy Hochul signed a new law that would mandate any factory manufacturer of a concrete culvert pay the (generally higher) “prevailing wage” to those who build it. The law would take effect later this year, perhaps June 1. But one or more of Enfield’s submitting bidders may have already factored the prevailing wage into their bids, thereby raising the price to Enfield.

And were Enfield to reject all of the bids just submitted and postpone construction until 2027, the prevailing wage mandate coupled with normal inflation could raise bid submissions by “40 to 50 percent,” Reaser told Friday’s meeting.

The possibility that Enfield might postpone the culvert project and pursue a cheaper, option dominated discussion during the hour-long January 16 conference. And the discussion revealed a split between the two Town Board members attending: Supervisor Stephanie Redmond, and Town Councilperson Robert Lynch (this writer).

In initial planning documents up until now, engineers had counted on installing—and only installing—a precast concrete culvert. The alternative, Board members learned at their Wednesday night meeting, is a “multi-plate aluminum box culvert.” Such a culvert is domed, it’s assembled on-site, and it rather resembles a Quonset hut buried under the road. The aluminum box is cheaper—a lot cheaper.

Although she made only an estimate and didn’t have in hand a firm bid, Hinickle Friday estimated the aluminum box would cost $266,486, just over 56 percent of what Jefferson Concrete’s bid had registered. Nonetheless, Hinickle and Reaser estimated that a metal box may cost $50,000 more to assemble on-site. Its parts bolt together. A concrete box is merely lowered into place by crane.

Bottom line: Friday’s estimates put the concrete culvert’s total project cost at $905,553. The aluminum culvert’s (admittedly more speculative) total price tag would reach$701,928. That’s a savings of $203,625, or about 22.5 percent, going the aluminum route.

Still, it’s not that simple. There’s an outside possibility that the New York State Transportation Department (DOT) may not accept the aluminum culvert’s selection. Pressed by Councilperson Lynch, Brian Reaser gave DOT’s acceptance likelihood at about “75 percent.” Reaser also warned that DOT could take up to nine months to make its decision.

What’s more, switching to the multi-plate aluminum design would require re-engineering the project. Reaser predicted redesign would take about one month to complete and would cost an additional $15,000 to $20,000.

Worst case: Were DOT to reject the aluminum option, a construction season would be lost, the current bids would have long-expired, and the “prevailing wage” mandate could push any fresh round of bids to $700,000 or beyond. Reaser said waiting until next year—and going concrete, by necessity—might inflate a $900,000 project to $1.125 Million.

But the culvert project is already way over budget. Its cost stands hundreds of thousands above the $693,866 that the WQIP grant had awarded.

At Friday’s meeting, Supervisor Redmond favored awarding the Jefferson Concrete Corporation bid and moving ahead with the project this year despite its higher cost. Redmond employed the “bird in the hand” analogy. To cover the funding shortfall, the Supervisor would tap—and significantly deplete—the Town’s budgeted $427,000 Bridge Reserve account.

Councilperson Lynch countered with a different opinion. “I’m willing to roll the dice and go aluminum,” he said. Lynch would bet on DOT’s acceptance of the metal plate. If DOT approved, the put-together aluminum plate box would “save the taxpayers $200,000.”

As Friday’s planning meeting closed, Lynch reduced the available options to four:

- Award the $471,600 Jefferson Concrete bid and utilize Bridge Reserves (or less likely, bonding) to cover cost overruns (Total = $905,553);

- Reject all current bids, reengineer for a multi-plate aluminum box, seek DOT’s approval, and bid the aluminum option, should DOT approve it (Total estimated = $701,928);

- Re-bid the concrete box culvert should DOT reject using an aluminum box (Total estimated = $1.125 Million); or

- Abandon the entire Bostwick Road culvert project until further notice.

The Enfield Town Board will weigh those options and likely decide among them Tuesday, January 20.

****

Writer’s note: In accordance with recent style changes, detailed previously, this Councilperson will increasingly refer to himself in these reports (albeit awkwardly) in the third-person.

###

Cloudy conclusions flow from Enfield Water Survey

Fewer than 25% “very interested” in public water; 45% very opposed

“I’m pretty sure at this point we’ve decided that we’re not looking into this any further because clearly it’s not affordable.”

Enfield Supervisor Stephanie Redmond, on prospects for municipal water, Sept. 17, 2025

by Robert Lynch; January 4, 2026

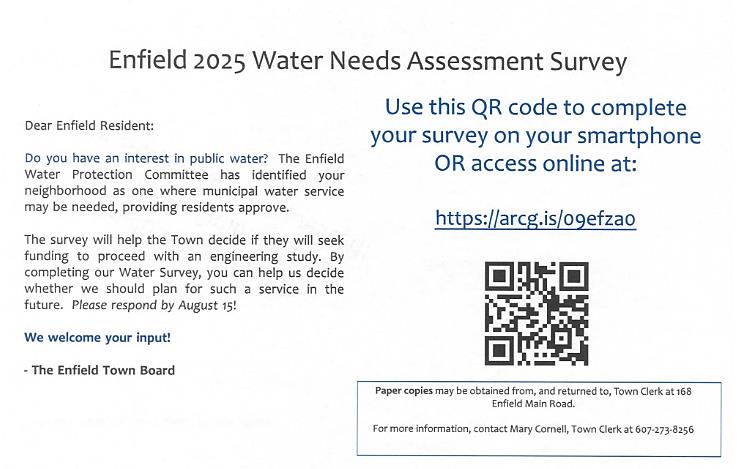

If those who conducted a limited-reach survey of Enfield residents last year were looking for public consensus toward building a municipal water or sewer system within the town, they didn’t find it.

True the sample size was tiny; small enough to make a statistician wince. That said, only 24.7 percent of respondents to a Town-authorized, geographically-targeted survey last summer in Enfield said they’d be “very interested” in changing to a municipal drinking water supply. Another 15.1 percent said they’d be “somewhat interested.” By contrast, a full 45.2 percent said they were “very disinterested” in making the change. An additional nearly ten percent said they were “somewhat disinterested.” That’s more than half the respondents turning thumbs-down.

“Opinions on municipal services are somewhat polarized,” former Town Board member Becky Sims, now New York State Manager of the water consulting group RCAP Solutions, advised the Town Board, at its special meeting September 17th. The consultant clearly stated the obvious.. Sims’ presentation got eclipsed that night by budget talks covering matters ranging from new tractors to health insurance rates to an administrative aide requested by the highway superintendent. Sims’ data got lost in the clutter.

And for months afterward, just about everything else in Enfield politics seemed more important to chronicle than the prospects for a town water district that’ll likely never happen. Still, before we launch headlong into the business of 2026, best we discuss the water survey’s findings and do it now.

By design, the Enfield Water Protection Committee, a semi-public advisory group with no real power, identified five sections of the town where it inferred public water was most in demand and concluded a municipal system was most affordable to build. The Town Board then commissioned Sims’ consultancy study. The only out-of-pocket cost, Board members were told, was the postage.

Any Enfield household stood eligible to participate. Prompts were posted on the Town website and paper copies were available at the Town Hall. But a select 368—and only 368—households were also mailed postcards alerting them of the survey’s existence. Ninety-three (93) responses came back during the survey period that ran in July and August. That’s a 25 percent response rate. “I would say it’s pretty great given the methods of outreach and the way that the survey was conducted,” Sims told the Town Board.

Yet the U.S. Census reports as many as 1,293 households exist in Enfield. So most people never got notified by mail. Fewer than three in ten of us received the cards.

The survey asked more than a score of questions. They dealt with homeowner water quality and quantity, resident interest in municipal water and/or sewer service, and the degree to which residents would be willing to pay for those services.

More than nine in ten respondents said their primary water supply comes from a drilled well. Five in six said their well never runs dry, even during droughts. Yet 65 of the 93 respondents (70%) reported hard water problems. Over 35 percent indicated orange or red staining. Twenty-eight percent said their water has sulfur.

“Water quality problems and treatment for those problems are widespread throughout this community,” Sims concluded. “Two-thirds of people report having at least one treatment system in place even if they’re not drinking the water,” the consultant stated. Forty-four percent of respondents say they drink their tap water untreated, but another 24 percent purchase their drinking water. (30% drink their own water, but treat it first.)

Nevertheless, while many in Enfield may agree their well water stands less than perfect, tapping into some future municipal system, and more importantly, paying for the privilege to do so, remains a reach too far for many.

Forty-two of 92 respondents (45.2%) said they’d be “unwilling” to pay anything to tap into a municipal water line, a number closely in parallel with the percentage opposed to municipal water in any instance. Another five percent said they were “unable to pay.” Thirty-three percent said they’d be willing to spend only less than $500 per year. Just 15 percent were willing to pay a greater amount.

“Willingness to pay is limited,” Sims conceded, “and I think that presents a real challenge for the Town if you were to want to pursue the development of a new water service area in earnest,” she said. “I think you’d be hard-pressed to get a new system built.”

Sims said that if more potential customers were willing to pay $500 to $1,000 per year for water—the survey said only 8.6% would do that—“I think your chances would be better.”

Sims speculated that had more people responded to the survey, the willing-to-pay percentages could have improved. Councilperson Jude Lemke also pointed out a potential survey flaw: If given a range of choices, people are apt to choose the lower-cost option.

But Enfield’s top elected leader has already made up her mind; resolved that given the results, any thought of setting up an Enfield water district now or in the near future has become a non-starter.

“I’m pretty sure at this point we’ve decided that we’re not looking into this any further because clearly it’s not affordable,” Redmond told a questioner from the meeting room’s gallery that night, the Supervisor, again—as she has the (unfortunate) tendency to do—imparting her own opinion and also assigning it to her four Board colleagues. “I think that was the point of the survey,” Redmond continued, “to see if it was going to be something that people really wanted and we should look into it farther, but clearly not only is there maybe not enough interest in it, but there’s not enough interest in paying for it.”

“That’s the value in doing these surveys,” Sims played off of Redmond’s conclusion. The alternative, Sims said, would be for Enfield to invest $30-50,000 on an engineering study; more technical, perhaps, yet still money wasted if a water district is something that neither the public nor the Town Board wants.

“For the Town being the size that it is, I’m not seeing that,” Sims weighed the prospect of advancing to an engineering probe.

But the reliability of a 93-respondent survey holds only the value of its underlying methodology. The Water Committee confined postcard distribution to just five Enfield roadways, most notably to Enfield Main Road (NY 327) from Route 79 south to the current Highway Garage, running through the heart of Enfield Center. Hayts Road (from Sheffield to Halseyville Road) was also carded. A large, eastern and central stretch of Route 79 was polled, as was at least a block of Van Dorn Road South.

“We can’t cover every house in Enfield,” Redmond stated, explaining why neither the entire town could be considered for water service or not every household polled. “So we targeted spots,” the Supervisor explained, where if a water district were built it would be “most likely to be built.”

That said, well-populated—and water-needy—Enfield neighborhoods remained inexplicably excluded.

“When I first looked at this map, what struck me most pronounced was there wasn’t a single response from Iradell Road,” this writer, Councilperson Robert Lynch, told Sims and fellow Board members, “and that’s in the shadow of the big blue tank,” reference made to the standpipe at Iradell and Van Dorn Roads. The standpipe is used by Ulysses to hold water it purchases from the intermunicipal Bolton Point system. Ulysses says the tank holds excess capacity that Enfield could access, should it build a pump house there.

True, Iradell is a town line road demarking Enfield from Ulysses. But Ulysses’ Supervisor has said that multi-town water districts can be created. Still, Enfield residents living along Iradell were never asked.

Moreover, long stretches is Halseyville Road were similarly ignored, leading to a minimal response.

“The water up there is downright terrible,” this Councilperson informed the Town Board. Shale rock limits well output there, the taste is bad, and wells run dry. Halseyville also borders the 33-lot Breezy Meadows subdivision. Breezy Meadows remains largely unbuilt, yet it’s destined for development—and the need for plentiful water—in the years ahead.

“People are concerned that their wells will run dry there when Breezy Meadows gets fully developed,” the Councilperson conveyed their worries. As for Halseyville Road, “I wish it had been surveyed. Too late now, but you might have gotten some responses up there.”

The relative demand for municipal water becomes “a self-fulfilling prophesy,” the argument held. And it does so when only select portions of the town receive postcards. “If people were not aware of it… they might not have known the survey was going to be taking place,” this Councilperson posited.

“Those are irrelevant to the survey,” Redmond countered as to the excluded neighborhoods, “because we were not considering putting any municipal water in their area because we can’t afford to,” she said.

Redmond’s argument may hold for sparsely-populated places such as uphill from Enfield Center. But what about Iradell and Halseyville Roads? What excluded them apart from arbitrariness?

Most discussion to date involving municipal water in Enfield has focused on drilling wells into the plentiful aquifer somewhere near Enfield Center. But a virgin water source like that would require a treatment plant and the staff to run it. An alternative would be to purchase already-treated Bolton Point water and then extend pipes down Iradell and/or Hayts Roads to Enfield Center, tapping Van Dorn, Rt. 79, Applegate and Halseyville Roads along the way. The idea earns nary a mention. Perhaps it should.

While the RCAP Solutions study focused mostly on water service, it also asked about municipal sewers. Sewage treatment would become a far heavier lift for a community Enfield’s size. Resident response about sewers paralleled that for water. Slightly more than one in five respondents expressed great interest in public sewers. Forty-three percent were very disinterested.

“Did anything surprise you,” a Board member asked Becky Sims as her 35-minute presentation wound to a close.

“I actually was a little bit surprised how many people were potentially interested in service,” the consultant responded, referring to the near 40 percent supportive of public water.

But it’s still a minority viewpoint. And perhaps more importantly, only a much-smaller minority would be willing to pay as much as it would likely cost to get public water to their homes. The polling showed that a quarter of Enfield residents buy the water they drink. Given survey results and the political lay of the land, expect that 25 percent to keep schlepping their water bottles for some time to come.

###